Ode to Zahir Raihan: The rebel who wrote, filmed, and fought for justice

Ode to Zahir Raihan: The rebel who wrote, filmed, and fought for justice

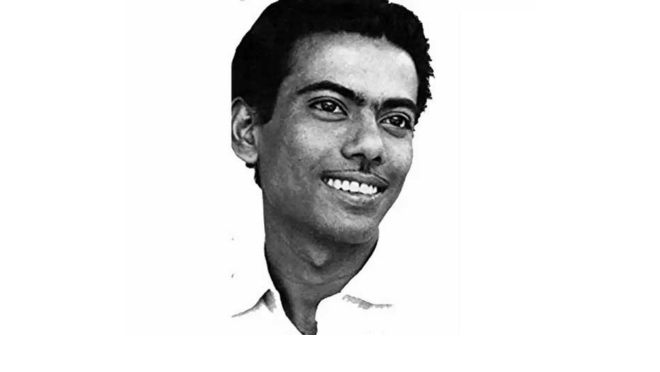

On 19 August, 1935, in the quiet village of Majupur in Feni, a boy named Abu Abdar Mohammad Zahirullah was born. Few could have guessed that in just 37 years, he would redefine the cultural and political imagination of a nation.

That boy would later be known to history as Zahir Raihan; a novelist, short story writer, journalist, political activist, and filmmaker whose pen and camera became weapons of resistance. His story is one of brilliance and tragedy, of dreams that lived beyond his own lifetime.

From the very beginning, Raihan showed an unusual sensitivity to the world around him. At fourteen, while studying at Sonagazi Amirabad B.C. Laha School, he published his first poem, Oder Janiye Dao, in Chotushkone magazine.

Even in this early work, his compassion for the oppressed and his rage against injustice were evident. Those emotions would go on to define both his literature and his cinema.

His elder brother, the writer and journalist Shahidullah Kaiser, was another shaping influence. In 1953, while studying at Dhaka College, Raihan joined the Communist Party under Kaiser’s encouragement.

Party members were each given new names, and Comrade Moni Singh, the party’s general secretary, chose “Raihan” for him. From that moment on, he became Zahir Raihan—the name that would enter the annals of history.

Though his name was new, his literary ambitions were already taking root. His first collection of short stories, Suryagrahan, was published in 1955 and established him as a fresh, bold voice in Bengali literature.

Over the years, he would go on to write eight novels and 21 short stories. These works focused largely on the middle class, their struggles, contradictions, and resilience in a rapidly changing society.

Zahir Raihan’s individuality is evident in his creations such as the last line of his novel Hajar Bochor Dhore, “Raat barche, Hajar bochorer purano shei raat” (The night is getting longer, the night is growing by the thousand years), and in Arek Falgun, “Ashchhe Falgune amra digun hobo” (We will be doubled by next spring). These very lines were echoed by participants in the recent July uprising, showing how his words of resilience continue to inspire generations of Bangladeshis to stand up for justice and change.

Zahir Raihan’s novels can be broadly categorized into three phases. Arek Falgun and Aar Koto Din are deeply rooted in history and politics, expressing his vision for a society free from oppression, with Arek Falgun standing out as the first novel inspired by the 1952 Language Movement. Hajar Bochor Dhore, his sole rural novel, offers a vivid depiction of life and landscapes in his native Feni district.

His later works, including Shesh Bikeler Meye, Borof Gola Nodi, Trishna, and Koyekti Mrityu, explore the hopes, struggles, and anxieties of urban life. At the same time, story collections like Ekushey February and Ekusher Golpo preserve the spirit of the Language Movement. Critics such as Humayun Azad have noted that Raihan may be the only Bangladeshi fiction writer whose entire literary journey was profoundly shaped by this movement.

While literature gave him a voice, cinema gave him a megaphone. Raihan began working as a journalist in 1950, joining Juger Alo, and later working for Khapchhara, Jantrik, and Cinema.

In 1956, he became the editor of Probaho. But his passion for storytelling soon moved him toward film. He started his cinematic journey as an assistant director in Jago Hua Savera (1957), and later worked with directors Salahuddin and Ehtesham, even writing songs for films. His directorial debut, Kokhono Asheni (1961), was followed by Sonar Kajol (1962), Kancher Deyal (1963), Behula (1966), Anwara (1967), and his crowning achievement, Jibon Theke Neya (1970).

He also pushed the boundaries of film technology in the region, directing Sangam (1964), Pakistan’s first color film, and Bahana (1965), its first CinemaScope film. Yet technical innovation was never his only goal. His films were deeply political, often using the personal as a metaphor for the collective.

Jibon Theke Neya, inspired by the Language Movement, is the finest example, a sharp political satire that used a family drama to symbolize authoritarian rule. The film earned the admiration of legends like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, and Tapan Sinha, who recognized Raihan’s brilliance as a filmmaker who could balance artistry with political commitment.

For Raihan, art and activism were inseparable. He had actively participated in the 1952 Language Movement, even being arrested on 21 February. Later, he threw himself into the Mass Uprising of 1969. And when the Liberation War broke out in 1971, he saw cinema as a weapon.

Abandoning his English-language project Let There Be Light, he created Stop Genocide—a documentary that exposed the atrocities committed by the Pakistani army. Screened in refugee camps and international rallies, the film played a crucial role in raising global awareness of Bangladesh’s plight. Critics later called it the beginning of Bangladesh’s documentary tradition. He also made A State is Born, further chronicling the struggle for freedom.

Despite financial hardship, Raihan donated proceeds from screenings of Jibon Theke Neya in Calcutta to the Freedom Fighters’ Trust. For him, art was not just about expression but also about sacrifice.

The war ended in December 1971, but the country remained scarred. His brother, Shahidullah Kaiser, was abducted by Al-Badr collaborators in the final days of the war. On 30 January, 1972, Zahir Raihan set out for Mirpur after receiving a tip that Kaiser might still be alive. He never came back. Mirpur, at that time, was still a stronghold of Razakars and Al-Badr forces. Eyewitnesses later confirmed that Raihan had been killed in a planned ambush that also claimed the lives of over a hundred army and police officers.

At just 37, Bangladesh lost one of its brightest stars. His disappearance left a wound that has never healed, and his body was never found.

And yet, despite his brief life, Raihan’s legacy is immense. He left behind novels, short stories, and films that continue to inspire and challenge. He was also a family man, married first to actress Sumita Devi, with whom he had two sons, and later to actress Shuchanda, with whom he had two more. His personal life, like his public one, was marked by both brilliance and turbulence.

What makes Zahir Raihan extraordinary is not just the quantity of his work, but the way he fused art with politics. His life is proof that creativity can be both beautiful and revolutionary, that words and images can be as powerful as weapons.

Even today, his works remind us of the sacrifices behind our freedom, the dangers of forgetting history, and the responsibility of youth to speak out against injustice. Generations of young rebels could still find in his writing and films a roadmap for resistance, showing that the spirit of rebellion never truly dies.

On his birthday, we remember him not merely as a writer or filmmaker, but as a rebel visionary who showed us how to dream of a freer, fairer world. We have lost Zahir Raihan more than fifty years ago, but his spirit lives on, in every word, every frame, and every act of resistance that refuses to be silenced.