56 research centres and counting: Pride or burden for Dhaka University?

56 research centres and counting: Pride or burden for Dhaka University?

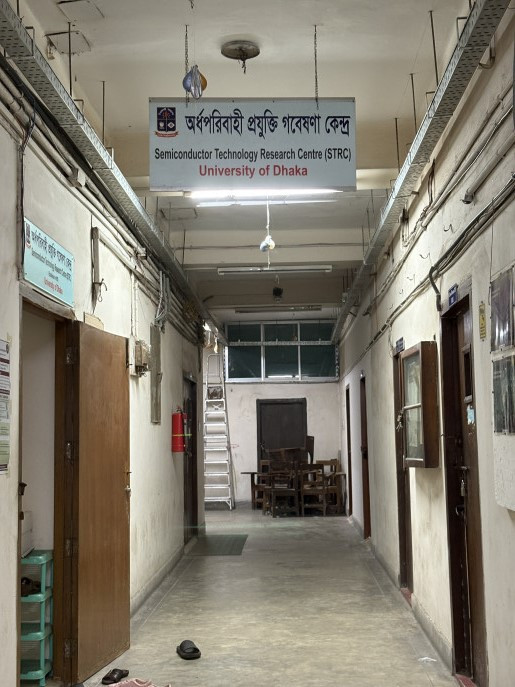

Dhaka University has an astounding number of research centres, 56 of them, and notable of them is the Semiconductor Research Centre. From solar panels to smartphones, computers to medical devices, semiconductors are indispensable.

Microchips are the most promising industry of the 21st century, the global market is expected to reach trillions of dollars. Recently, the Bangladesh Semiconductor Industry Association unveiled a roadmap to export one billion dollars’ worth of semiconductor chips and devices by 2030. But to get there, the country will need 10,000 engineers skilled in semiconductor design.

It was the late Professor Sultan Ahmed of Dhaka University’s Physics Department who dreamt of this three decades ago. He foresaw the global potential of semiconductor chips and went on to establish the Semiconductor Research Centre,” said Professor Kamrul Hassan Mamun of the department. He added, “Who could have imagined setting up a semiconductor research centre back in 1985? The word itself was barely familiar then. Sultan Ahmed was a visionary and a dedicated researcher.”

“Had the centre received the necessary support — equipment, funding, post-doctoral fellows, PhD researchers, and a dedicated director — it could have produced thousands of engineers over the past four decades. But despite Dhaka University having 56 research centres, very few are active due to various limitations. Even many world-renowned universities do not boast such a large number of centres,” said Professor Kamrul Hassan Mamun.

Professor Mamun recently stepped down as head of the Bose Centre — a post any devoted scientist at Dhaka University would normally consider priceless. He left, however, citing a total lack of challenge. In his own words: ‘The Bose Centre is fifty-one years old. Its output? Hardly anything. Even before my time, did it truly exist? This so-called science factory has a single office room, two staff members, and a director.’”

He continues, “The director’s job here mostly involves handing out monthly fellowship checks to a handful of students and signing stacks of papers every day. There are no in-house post-docs, no PhD fellows, and no dedicated researchers. Those receiving fellowships continue their research in their own departments. Beyond distributing money, the Bose Centre does nothing — work that could easily be handled by officials at the registrar’s office. So, what’s the point of attaching a scientist like Satyendra Nath Bose’s name to this centre (Bose Centre for Advanced Study and Research in Natural Sciences)?”

Birthplace of Quantum Statistics

In 1924, Satyen Bose, a faculty member of the same university, astonished even Einstein by developing the theory of quantum statistics. Later, the Bose-Einstein theory opened new frontiers of research for scientists across the globe.

Professor Mamun felt a surge of excitement when he was asked to take charge of Bose Centre for Advanced Study and Research in Natural Sciences. He envisioned reviving the near-defunct research centre, bringing it back to life.

Reviving the research centre has become crucial, to honour the legacy of Satyen Bose. Professor Mamun was deeply impressed by the dynamism at Kolkata’s S.N. Bose Centre for Basic Sciences, where scientists dedicate day and night to research, supported by state-of-the-art facilities and equipment. Drawing inspiration from this, he submitted a detailed action plan for the centre to the university authorities.

The authorities have understood a little, overlooked much, or perhaps ignored it altogether. For them, votes and political manoeuvring take precedence over the rise or fall of the Bose Centre. What currently exists is a dilapidated room, whereas achieving meaningful results would require an entire building like Karzon Hall. Frustrated by these realities, Professor Mamun chose to resign.

The Chromosome Centre

The university’s Chromosome Centre was established in 2014 through the personal initiative of Professor Sheikh Shamim Ul Alam. The centre has no separate address; the director’s office serves as its official location. This year, it received a total allocation of Tk12 lakh. After covering ancillary expenses such as staff salaries, Tk8 lakh is available for research. This amount is divided among four researchers—mostly junior faculty—at Tk2 lakh each. Typically, research topics and preliminary proposals are reviewed by two reviewers. If there is a difference of opinion between them, the matter is referred to a third reviewer for a final assessment.

At a seminar held near the end of the fiscal year, researchers present their papers. Early studies focused largely on variations in chromosome number, size, and shape. Current research involves DNA and proteins, alongside genome sequencing and gene transfer studies. Professor Dr. Mohammad Nurul Islam has been serving as the director of the Chromosome Centre since 2021. He completed his postdoctoral research in Sweden.

He said, “When a proper environment for research is created, researchers will have no hesitation in returning to the country. Although funding for the Chromosome Centre has increased compared to before, it still takes a long time for the allocated money to reach us from the Registrar’s building. This shortens the time available for research and affects its quality. Research in chromosomes or biotechnology is somewhat like taming an elephant. All the necessary enzymes have to be imported from abroad, which are already costly, and import duties make them even more expensive. Despite all these challenges, I believe the centre is much more active compared to other research centres at Dhaka University.”

At this stage, we asked Dr Nurul Islam, “Assuming the Chromosome Centre is ahead compared to other research centres at the university, how would you rate it on a global scale?” Nurul Islam replied, “There’s really no basis for comparison in this case; I honestly cannot give it a score.”

For the 2025–26 fiscal year, Dhaka University has been allocated a budget of Tk1,035.45 crore. Of this, Tk20.07 crore had been set aside in the 2024–25 session for the university’s research centres. For 2025–26, the allocation has been slightly increased to Tk21.57 crore, representing only 2.8% of the total budget.

It would be better if inactive centres were closed

Like Professor Mamun, Dr Islam also believes the allocation is far from sufficient. If the inactive centres were closed or merged, it could create a somewhat more manageable situation. For instance, there is an opportunity to merge the Chromosome and Biotechnology Centres, as both conduct similar research.

Professor Jasim Uddin, director of the Higher Humanities Research Centre, said, “Most of these research centres are unnecessary, as only a few are active. Even having just one centre per faculty would likely produce better research than the current setup.”

How to make a research centre effective

When asked what else is needed to make a research centre effective besides funding, Professor ABM Shahidul Islam, director of the Bureau of Business Research (BBR), stressed the importance of a full-time, dedicated director—someone who cannot be burdened with other responsibilities. Adequate infrastructure and a skilled workforce are also essential.

Professor Tayebur Rahman, acting dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences and head of the Advanced Social Science Research Centre, expressed a similar view, saying, “There are so many centres, yet there is no staff, no rooms, and not even enough computers.”

Despite numerous constraints, the Bureau of Business Research (BBR) has gained momentum over the years, says its director, Professor ABM Shahidul Islam. The institution’s researchers have conducted studies on a wide range of topics, including the dynamics between advertising agencies and their clients, industrial workers’ safety in Bangladesh, the impact of tourism on daily life, and influencer marketing.

Some More Research Centres

In addition to the previously mentioned centres, the university also hosts several others, including the Arberi Culture, Archives and Historical Research Centre; Bangamata Sheikh Fazilatunnesa Centre for Gender and Development Studies; Bangladesh-Australia Centre for Environmental Research; Biomedical Research Centre; Bureau of Economic Research; Centre for Climate Change Study and Resource Utilization; Centre for Corporate Governance and Finance Studies; Centre for Development and Institutional Studies; Centre for Genocide Studies; Centre for Development Policy Research; Centre for Education Research and Training; Centre for Microfinance and Development; Centre for Project Management and Information System; and Centre for Urban Resilience Studies, Centre on Budget and Policy; Centre for Advanced Research in Arts and Social Sciences; Centre for Advanced Research in Humanities; Centre for Advanced Research in Strategic Human Resource Management; Disaster Research, Training and Management Centre; Dr. Sirajul Haque Centre for Islamic Research; Energy Park; Innovation and Creativity Centre (ICE); International Centre for Ocean Governance; Kotler Centre for Marketing Excellence (KCME); Nazmul Karim Study Centre; Nazrul Research Centre; Neuroscience Research Centre of Dhaka University (NRCDU); Organic Pollutants Research Centre; Professor Dilip Kumar Bhattacharya Research Centre; Refugee and Migratory Movement Research Unit; Renewable Energy Research Centre (autonomous under the Faculty of Science, DU); Scandinavian Study Centre; Semiconductor Technology Research Centre; Centre for Advanced Legal Studies; East Asia Study Centre (EASC); University-Industry Alliance, among others.

Each faculty hosts multiple research centres, while some are department-based. As a result, although the number of centres has grown, the university has yet to develop the capacity to ensure their effective functioning.

From generation to generation

At the end of the discussion, we asked Professor Kamrul Hasan Mamun how the country benefits from research activities. He replied, “Not just the country, but the entire world benefits from research. Bose-Einstein theory still helps us understand the behaviour of matter and light—and may continue to do so for hundreds of years to come. The results of each study are, in essence, passed down from generation to generation, opening new doors along the way. Developed countries understand this, which is why they progress, while we remain backward because we do not.”