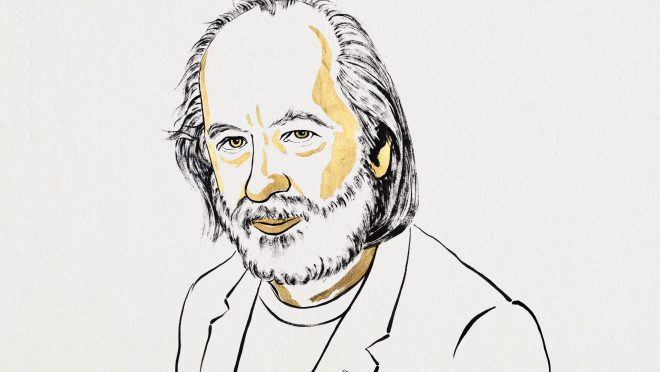

László Krasznahorkai: The slow apocalypse of a restless mind

László Krasznahorkai: The slow apocalypse of a restless mind

While many of us stumbled over the name László Krasznahorkai the first time we heard it, and perhaps weren’t familiar with his works, the Booker Prize–winning Hungarian author has long been considered a favourite contender for the world’s most prestigious literary honour — the Nobel Prize in Literature.

When the Swedish Academy announced that the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2025 would go to László Krasznahorkai, readers across the world paused, not because they were surprised, but because they knew the world had just caught up with a man who had been writing about its collapse for decades.

Now, the Nobel committee states that László Krasznahorkai was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art.”

Born in 1954 in Gyula, a small town on the Hungarian–Romanian border, Krasznahorkai writes the kind of novels that feel like they are being written against time itself — long, looping, obsessive sentences that circle despair and faith, beauty and ruin, until the reader is dizzy but awake.

His prose doesn’t move in straight lines. It meanders, like a desperate prayer or a river running through fog, searching for meaning in a landscape that no longer promises any.

In his interview with The Yale Review, he spoke of the apocalypse not as a thunderclap, but as a condition. “The apocalypse,” he said, “is not coming — it has already begun.” For him, the end of the world is not an event but an atmosphere.

We live inside it; we breathe it. The internet scrolls, the cities grow, and we keep pretending that the present is a bridge to something better. But Krasznahorkai insists that there is only now, and it’s crumbling as we speak.

Consider his novels — Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, War and War; they are monumental in their despair. They demand the reader’s patience, not as punishment, but as initiation. In Satantango, an abandoned village waits for a mysterious man named Irimiás to return and save them; instead, he exposes their delusions.

The novel unfolds in twelve chapters, looping back and forth in time like a tango, and the rhythm feels both hypnotic and claustrophobic. If Franz Kafka wrote nightmares, Krasznahorkai wrote the insomnia that follows.

The Nobel Committee praised him for his “visionary narratives that illuminate the struggle for meaning in a fragmented world.” But that sentence, like all official sentences, only hints at the quiet terror in his work.

Krasznahorkai is not merely chronicling a broken world — he is searching for the sacred within its ruins. His long sentences, often stretching across pages without a single full stop, mimic the unbroken stream of consciousness, the breathless continuity of existence. To read him is to be reminded that literature can still resist the algorithmic pace of our times.

For young readers, especially those who grew up in an age of speed — of notifications, soundbites, and content — Krasznahorkai offers a kind of radical slowness. His novels refuse to be skimmed. They ask for stillness, for solitude.

And perhaps that is why his work feels so strangely urgent now. To read him is to practice the forgotten art of attention.

Krasznahorkai’s path to global recognition was anything but smooth. Under Hungary’s communist regime, his early manuscripts faced censorship, and for years he lived a nomadic life — moving between Berlin, New York, Kyoto, and countless other cities.

His translators, especially George Szirtes and Ottilie Mulzet, became his closest collaborators, carrying the rhythm of his Hungarian sentences into English with extraordinary care. Through them, his voice reached a wider world: melancholic, ironic, endlessly searching.

In The Melancholy of Resistance, which inspired Béla Tarr’s haunting film Werckmeister Harmonies, a town descends into chaos when a circus arrives with a dead whale and a mysterious “Prince.” The story feels biblical and absurd at once — a parable about collective hysteria and the fragile illusion of order. Krasznahorkai’s apocalypse, again, is not about explosions. It is about the quiet corrosion of belief.

Yet, there is an odd kind of tenderness in his vision. In War and War, a man obsessed with preserving a mysterious manuscript travels to New York, convinced that he must upload it to the internet before humanity destroys itself.

The novel ends with both destruction and salvation, suggesting that art — or the act of writing itself — might be the last refuge of meaning. Krasznahorkai’s characters rarely find peace, but they do find purpose. That, he seems to say, is enough.

When DW reported his Nobel win, Hungarian readers celebrated with restrained pride. Krasznahorkai has long been a figure of myth — an author who writes slowly, avoids the spotlight, and speaks of transcendence in an age allergic to mystery. His Nobel is not just a national honour; it’s a reminder that literature still has space for difficulty, for the kind of writing that doesn’t flatter the reader but transforms them.

And what does it mean for young readers to encounter such a writer now? Perhaps it is an invitation — to read not for distraction but for depth, to follow sentences that wander without promise of conclusion, to find beauty in discomfort.

Krasznahorkai’s novels are not stories you consume; they are experiences you undergo. You begin reading them as a reader and end as a witness.

In his Nobel biography, the Academy notes that Krasznahorkai studied law before turning to literature, that he was influenced by Eastern philosophy, and that his works explore “the tension between chaos and order, despair and transcendence.”

But these are merely coordinates. To read him is to walk through a labyrinth, where the walls are sentences and the exit, if it exists, is enlightenment.

He once said that his writing is an attempt to “describe the indescribable.” That may sound impossible, but impossibility is precisely his point. In a time when words are often used to simplify, Krasznahorkai uses them to restore complexity — to make us see the world again, not as a feed of fleeting updates, but as a trembling, infinite thing.

If you are a young reader standing at the edge of your own uncertainty — unsure of where the world is heading, or where you belong in it — Krasznahorkai’s novels might not give you answers. But they will give you language for your confusion, and that is its own kind of solace. His work reminds us that literature isn’t meant to fix the world; it’s meant to bear witness to it, sentence by sentence.

Perhaps that’s what the Nobel Prize saw in him this year — not just a master of prose, but a philosopher of the slow apocalypse we are all living through. Krasznahorkai writes as if time were running out, and maybe it is. But in his pages, at least, the world still holds together, one dizzying sentence at a time.