Frankenstein: Why Mary Shelley’s 200-year-old horror story still remains misunderstood

Frankenstein: Why Mary Shelley’s 200-year-old horror story still remains misunderstood

As Guillermo del Toro’s new film featuring Oscar Isaac and Jacob Elordi is released in cinemas, one might wonder why the true message of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) has remained overshadowed by its success for more than two centuries since its publication, as noted by Rebecca Laurence in her article ‘Frankenstein: Why Mary Shelley’s 200-year-old horror story is so misunderstood’ published on BBC.

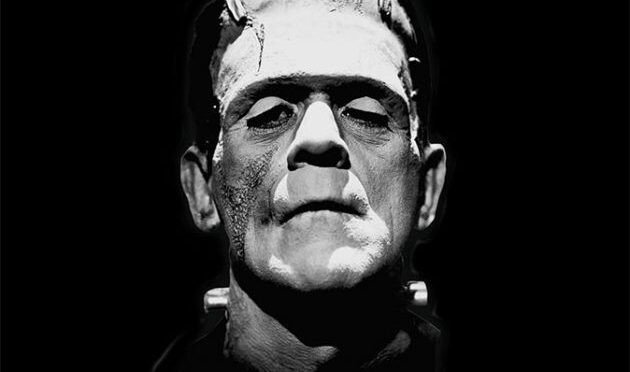

“It’s alive! It’s alive!! It’s alive!!!” – Frankenstein (dir: James Whale, 1931)

A stormy beginning

One night during the unusually cold and wet European summer of 1816, a small group of friends gathered at the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva.

“We will each write a ghost story,” Lord Byron declared.

Among those present were Byron’s physician, John Polidori, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and 18-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin – later Mary Shelley.

“I busied myself to think of a story,” she later recalled, “one which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature and awaken thrilling horror.”

From this challenge emerged Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus – the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young student of natural philosophy whose reckless ambition drives him to animate a lifeless body, only to recoil in terror and disgust at his own creation.

Part science fiction, part Gothic horror, part tragic romance, and part moral parable, Frankenstein stands as a work stitched together from multiple genres into a single, electrifying form. Its twin tragedies — the peril of “playing God” and the pain of parental rejection — remain deeply relevant to this day.

From page to pop culture

Mary Shelley’s “creature” and her “mad scientist” are among the most enduring archetypes in modern storytelling. From the moment they lurched off the page, they have haunted stage and screen alike, becoming cornerstones not only of horror but of cinematic history itself.

From Thomas Edison’s eerie 1910 short film to Universal Pictures’ and Hammer’s classic adaptations, from The Rocky Horror Picture Show to 2001: A Space Odyssey, Frankenstein has inspired endless reinventions. There are Italian and Japanese versions, a Blaxploitation spin-off titled Blackenstein, and reimaginings by Mel Brooks, Kenneth Branagh, and Tim Burton.

Its influence stretches across media: comic books, video games, television, novels, and even music — from Ice Cube and Metallica to T’Pau’s China in Your Hand:

“It was a flight on the wings of a young girl’s dreams / That flew too far away… And we could make the monster live again.”

Now, decades later, Guillermo del Toro has realised his lifelong dream of adapting Frankenstein for the screen — a project over thirty years in the making.

The moral of the myth

As a parable, Frankenstein has been interpreted through countless lenses — as both a warning against and an argument for revolution, slavery, vivisection, empire, and the moral boundaries of science. The prefix “Franken-” has entered modern vocabulary as shorthand for any anxiety about scientific progress — from atomic weapons to GM crops, stem-cell research, and now artificial intelligence.

“All them scientists – they’re all alike. They say they’re working for us but what they really want is to rule the world!” – Young Frankenstein (dir: Mel Brooks, 1974)

Mary Shelley captured a world on the brink of modernity. Though the word “scientist” had yet to be coined, the anxieties surrounding human power and invention were already palpable. As biographer Fiona Sampson notes,

“With modernity comes a sense of anxiety about what humans can do and particularly an anxiety about science and technology.”

Shelley channelled that fear into fiction, fusing philosophical debates with imagination in a way that felt startlingly plausible — and has remained so ever since.

In 1816, at the Villa Diodati, she and Byron had discussed the “principle of life.” Experiments such as Luigi Galvani’s electrical stimulation of frog legs — and Giovanni Aldini’s macabre demonstrations on human corpses — had ignited public fascination with reanimation. These influences, combined with the ideas of thinkers like Sir Humphry Davy and Shelley’s own father, philosopher William Godwin, gave rise to a story that examined not the mechanics of life, but its moral cost.

“With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.”

The novel’s “science” is deliberately vague, timeless enough to reflect the fears of every new technological age.

The monster and the myth

The creature’s awakening —

“I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.”

— remains one of literature’s most chilling scenes. Hollywood seized on this image, transforming the creature into a mute monster and Victor into the archetypal mad scientist. As Christopher Frayling notes in Frankenstein: The First Two Hundred Years, early stage plays and films distilled Shelley’s complex narrative into spectacle, adding now-familiar details like the assistant, the laboratory, and the cry of “It lives!”

James Whale’s 1931 film, starring Boris Karloff, solidified the myth.

“Frankenstein [the film] created the definitive movie image of the mad scientist… It began to look as though Hollywood had actually invented Frankenstein.”

Yet in doing so, it obscured Shelley’s empathy — her creature was no mindless fiend but a being capable of sorrow, intelligence, and longing.

“I ought to be thy Adam”

Shelley’s novel gives the creature a voice — even a soul. Among the book’s three narrators, his plea remains unforgettable:

“Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed… I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.”

His tragedy is rooted in rejection — by his creator, and by a world that cannot bear to look at him. Many have read this as a metaphor for parental abandonment, a theme close to Shelley’s own life: she lost her mother at birth, buried her infant daughter shortly before writing Frankenstein, and was caring for her pregnant stepsister at the time. The story, written over nine months, is steeped in grief and the cycle of creation and loss.

“The way that we sometimes identify with Frankenstein… and partly with the creature — they are both aspects of ourselves,” says Fiona Sampson. “They both speak to us about being human. And that’s incredibly powerful.”

A new creation

Del Toro’s adaptation restores this humanity. Before its Venice premiere, he told Variety that his film — starring Oscar Isaac as Victor Frankenstein and Jacob Elordi as the creature — is less horror than an exploration of “the lineage of familial pain”, depicting Isaac’s character as an abusive father who abandons his child.

“He was an outsider. He didn’t fit into the world,” Del Toro said, identifying with the creature himself. “Frankenstein is a song of the human experience… There’s so much of my own biography in the DNA of the novel.”

When accepting his 2018 Bafta for The Shape of Water, he thanked Mary Shelley:

“She picked up the plight of Caliban and she gave weight to the burden of Prometheus, and she gave voice to the voiceless and presence to the invisible…”

The myth endures

When Mary Godwin first conceived her story that summer of 1816, she could never have imagined its reach — shaping culture, science, and the very language of fear for centuries to come.

“And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper,” she wrote in 1831.

Her creation did prosper — growing beyond “thrilling horror” into a myth of its own. Two hundred years on, Frankenstein remains alive, not merely as a monster tale, but as a haunting mirror held up to humanity itself.