Ode to John Keats: A life in borrowed time and a friendship in elegy

Ode to John Keats: A life in borrowed time and a friendship in elegy

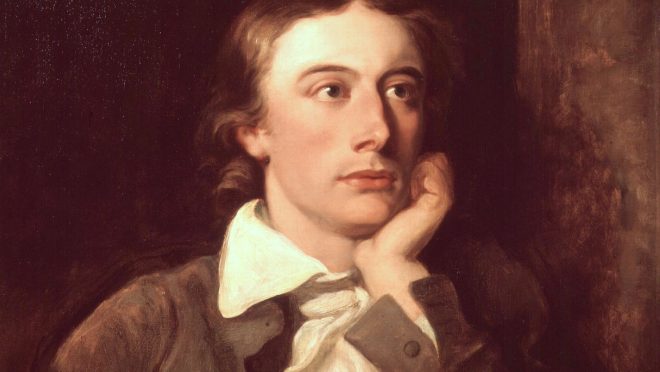

There’s a particular ache that comes with reading John Keats, the sense that you’re witnessing something magnificent being created just moments before it’s lost forever. Today, 31 October, marks the 230th birthday of this man who lived on borrowed time, a poet who poured the genius of a full lifetime into a handful of years. His story is not just one of solitary genius, but of a powerful friendship with Percy Bysshe Shelley, who would define his legacy long after his voice fell silent.

The race against time

Keats knew the clock was ticking for him. Tuberculosis, the “family disease,” had taken his mother and brother. The shadow of it followed him, sharpening his senses and lending a desperate urgency to his work. In his short span of life, he produced an astonishing collection of masterpieces, the great Odes including “Ode to a Nightingale”, “To Autumn” and “Ode on a Grecian Urn”, alongside works like “The Eve of St. Agnes”, “Lamia”, as if trying to outrun his own fate. For Keats, death wasn’t just an end. It was a release from the “weariness, the fever, and the fret” of a life he knew was slipping through his fingers.

The poet of beauty

In the face of this mortality, Keats turned to beauty as his anchor. He wasn’t just a poet who wrote about beautiful things; for him, beauty was truth itself. It was the only thing that could withstand the decay of the physical world. Though mocked by critics in his time for being overly sentimental and lacking classical restraint, his work later emerged as a cornerstone of English Romanticism. His famous declaration, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”, founded the philosophy of his life as he found permanence in art that life could never offer.

Acceptance of mysteries

To balance this intense pursuit of beauty with the harsh reality of his life, Keats developed a remarkable concept: “Negative Capability”. He defined it as the ability to be in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason. In simpler terms, it’s the wisdom to accept that some mysteries can’t be solved, and that’s okay. Perhaps this is why unheard melodies are deemed much sweeter to him. The imagination, the possibility of what it could be without getting to the bottom of it – that’s where the real magic lives for Keats.

A farewell by Shelley

This embrace of mystery perfectly frames his relationship with Percy Bysshe Shelley. They were an unlikely pair, the apothecary’s son and the aristocratic radical, bound by genius and circumstance. When Keats died in Rome at just 25, Shelley was devastated. He channelled his grief into “Adonais,” a soaring elegy for Keats. The excruciating loss Shelley had gone through is etched in the line: “No more let Life divide what Death can join together.”

An eerie twist of fate

In a turn of events that feels almost uncanny, Shelley drowned just one year after publishing his elegy and the death of Keats. When his body was recovered, a copy of Keats’s poems was found in his pocket. It was a final, heartbreaking connection between two souls bound by art. The perfect and tragic symmetry of their story, of two young poets where one mourned the other, only to follow him so soon after, defies easy explanation. And perhaps that is the point. The truest way to honour their friendship is through Keats’s own greatest gift to us: the wisdom to embrace the mystery, to find the beauty in the unanswered question, and to recognise that some bonds are too profound for even death to break.

A thing of beauty is indeed a joy forever, and in John Keats, we were given one of the most timeless joys in all of literature. His voice, though stilled too soon, remains forever young, forever warm, and forever a truth we need to know.