Celebrating World Cinema Day: Cinema as a witness of time

Celebrating World Cinema Day: Cinema as a witness of time

Long before fiction, plot and performance took over the screen, cinema functioned as a record of work, movement, ritual, conflict and everyday life.

Now, the history of cinema is celebrated around the globe every year on 28 December, and one might argue that it is done so wrongfully. Because, when we speak of the world cinema day, we often narrate it as the day when the first cinema was created. But the date points to the event when Lumière brothers held their first paid public screening in Paris. They screened a series of short scenes from everyday French life, but it’s not that moving images were not created before that screening.

Similarly, when speaking of the Lumière brothers, they are often described as the inventors of cinema. While this comes from a famous misconception, the real question is why we prioritise the 1895 screenings over earlier milestones in the history of cinema, such as Louis Le Prince’s Roundhay Garden Scene, filmed in October 1888.

Le Prince’s filmmaking process inspired thousands—including the likes of Thomas Edison and Georges Melies. Edison began creating motion pictures that recorded lived realities; athletic displays, Native American traditions, rituals, different forms of dance, even scandalous dance performances became the subject of his cinema. Films such as Dickson Greeting, Newark Athlete, and Men Boxing (1891) were among the first moving images ever recorded on celluloid.

They prove that from the very beginning, cinema was entangled with spectacle, labour, gender, and, most importantly, the political landscape of a society.But the most interesting fact is the term used for such films. Early film historians use the term ‘actuality’ to describe these short non-fiction films produced during the first decade of motion picture history. In modern discourse, the term itself holds connotations that extend far beyond the technical definitions assigned by early historians. We now understand recording itself as a political act. Society dictates who, what and how things are to be recorded. And so the term ‘actuality’ serves as a fitting designation for cinema, since it possesses the unique capacity to capture the moral and social truths of its time.

Initially, individuals would peer through the hole of a Kinetoscope to view realities that were already visible to them. Perhaps that experience was able to offer a perspective that the unmediated reality could not.

Either way, as Edison’s Kinetoscope gained popularity, the demand for new subjects expanded. War and disaster soon became central subjects. Through these films, cinema functioned as an early visual archive of modern history. Yet despite this vast documentary impulse, Edison’s cinema remained mostly private. In theory, there is nothing inherently wrong with cinema being viewed individually. Many modern filmmakers deliberately resist open commercial circulation and prefer to screen their films in closed, controlled, or semi-private contexts. Even then, the experience is often shared among like-minded peers.

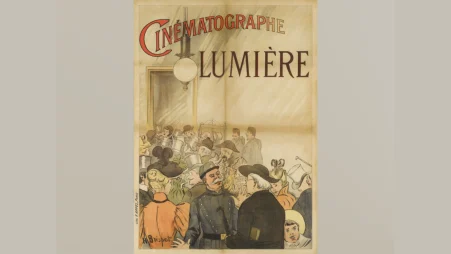

However, the Kinetoscope was restricted to a single viewer at a time. This changed decisively with the invention of the Cinematographe, which, for the first time, enabled cinema to be screened for a public audience.

The Lumiere brothers, Auguste and Louis, arranged the first public screening of a movie in Paris in 1895—featuring films like Workers Leaving the Lumiere Factory.

This event transformed the possibilities cinema had to offer by creating a collective viewing experience. While the Kinetoscope functioned as a voyeuristic device, the Cinematographe became a democratic one.

Cinema moved from the peephole to the screen, from individual curiosity to shared spectatorship. Even the word ‘cinema’ was not originally intended to describe the flickering light alone; it was the name of the space where movies are to be screened. To name the art after the space it occupies is to admit that its very soul is social—that it exists not in the isolation of the eye, but in the collective breathing of the crowd.

Thus, early cinema was defined by two foundational qualities: the ability to document reality and the power to reach the masses. While Le Prince and many others can be accredited as the first filmmakers, history chooses to remember the Lumière brothers for establishing cinema as a public, social event on December 28, 1895.

On World Cinema Day, we remember the social nature of cinema to understand the power the screen holds to remember, narrate, and deliver. It is a vessel designed to hold what the world tries to discard; memories of injustice, the cold weight of violence, and the silent machinery of exploitation.

And it does more than just narrate loss and grief. It carries our everyday dreams and stubborn hopes, and that persistent ache for a better world, delivering them from the individual consciousness to the public eye. In times like these, the philosophical argument regarding the ethics of a filmmaker or a film activist is no longer a theoretical debate, but a social reality—a burden of truth that the artist must carry