Why dopamine isn't really a 'pleasure chemical'

Without dopamine, the brain does not actively seek experiences or goals.

Why dopamine isn't really a 'pleasure chemical'

Without dopamine, the brain does not actively seek experiences or goals.

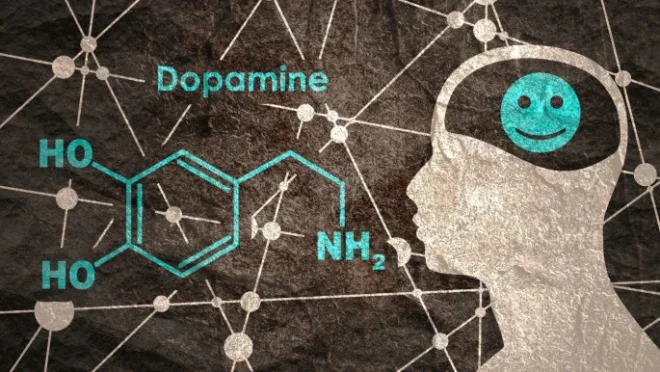

Dopamine is often casually labelled the brain’s “pleasure chemical”, but neuroscientists say this popular idea misses the point, and may even explain why people so often feel conflicted, restless and dissatisfied with their own behaviour.

In an in-depth analysis published by the BBC, neuroscientist Nikolay Kukushkin argues that dopamine does not simply make people feel good. Instead, it plays a far more complex role in motivation, learning and the persistent human drive to seek “more”, even at the cost of contentment.

According to Kukushkin, humans frequently feel misaligned with their own minds – drawn to unhealthy habits, bored by stability, and constantly chasing fulfilment. This, he suggests, is not a flaw of modern life or civilisation but a built-in feature of the brain’s design, shaped long before agriculture or technology.

At the centre of this design is dopamine, a neurotransmitter that pushes the brain out of what scientists describe as a “dark room” – a state where doing nothing would otherwise be the easiest path to mental stability. Without dopamine, the brain does not actively seek experiences or goals.

Historical evidence from a rare condition known as encephalitis lethargica illustrates this starkly. Patients affected by the disease in the early 20th century remained awake but largely motionless, unable to initiate action. When some were later treated with L-DOPA – a dopamine precursor – they briefly regained movement, speech and motivation, before slipping back into inertia.

This, Kukushkin explains, shows that dopamine does not merely enhance pleasure but enables action itself.

“Removing dopamine from the brain doesn’t simply paralyse it,” he writes. “It puts it in the dark room – a state of nonaction and nonexperience.”

Modern neuroscience has also challenged the idea that dopamine produces enjoyment. Studies involving both humans and animals show that dopamine-boosting drugs increase effort and focus, but not happiness. Instead, dopamine appears to reinforce behaviours and thoughts linked to success, particularly when that success is unexpected.

Rather than a simple “do more of that” signal, dopamine is triggered most strongly by outcomes that are “better than expected”. In this sense, it acts less as a reward and more as a signal demanding attention and explanation.

Kukushkin proposes that dopamine may be better understood as an imperative message to the brain: “figure this out”. The surge compels the brain to analyse what led to an unexpected outcome and to act again, rather than passively accepting reality.

This mechanism also helps explain why uncertainty is so addictive. Experiments with animals show that unpredictable rewards provoke far more persistent behaviour than predictable ones. The same principle underpins the appeal of gambling and social media, where likes, wins and validation arrive at random spells.

“Dopamine does not mark up the world into ‘good’ and ‘bad’,” Kukushkin notes. Instead, it flags surprises – pushing people to pursue patterns, even when none exist, and ensuring that satisfaction is always temporary.

From an evolutionary perspective, this restlessness has clear advantages. Creatures driven to explore, adapt and seek novelty are more likely to survive in changing environments. Peace of mind, Kukushkin suggests, may be optional, but curiosity and dissatisfaction are not.

In the end, dopamine’s role may not be to make people happy, but to keep them moving.