Banteng’s vanishing act: Fact, fiction and forgotten wildlife

Banteng’s vanishing act: Fact, fiction and forgotten wildlife

For decades, a quiet debate has simmered in Bangladeshi wildlife circles: did the banteng — a critically endangered species of wild cattle now only found in Southeast Asia — ever truly roam the Chittagong Hill Tracts?

Bantengs, in books, are labelled as extinct in Bangladesh for about a century. Many conservationists, even respected ones, have dismissed the idea outright, arguing that no hard proof exists of their presence in Bangladesh. Some have gone so far as to suggest that any ‘banteng’ sightings in the region were simply gaurs misidentified by the untrained eye.

But the absence of recent sightings does not erase the past. In fact, colonial-era literature provides clear, detailed accounts of bantengs in what is now southeast Bangladesh, as well as adjacent areas of Manipur in India and Arakan, Chindwin, and Sagaing in Myanmar. And the descriptions are so precise — often contrasting banteng with gaur — that confusion between the two is unlikely.

Recently, I was contacted by the Banteng Green List Assessment team to provide information on the species’ historical presence in the region, ideally after the 1500s. It struck me as the perfect opportunity to finally set the record straight against all the ‘wrong guesses’ that have been passed along as fact, seeding doubts and erasing the history of an already extinct animal.

Hunting for history in old books

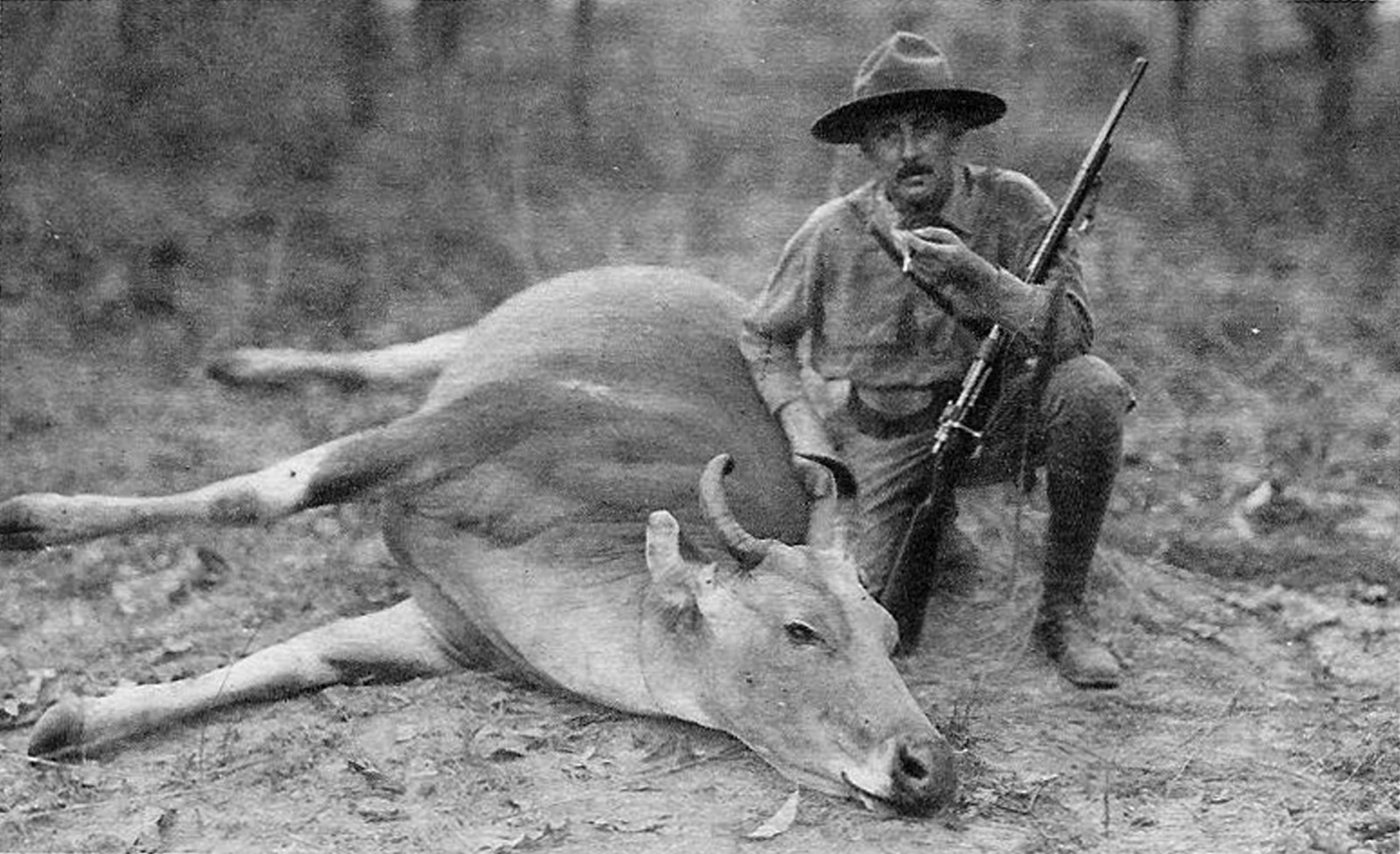

Banteng killed during the colonial period. Date and place unknown. PHOTO: COLLECTED

The best place to begin tracking extinction is often in colonial hunting chronicles and gazetteers. For a wildlife biologist, these hunting stories can be heavy to take on, but they remain invaluable records.

My literature review took me deep into the works of 19th- and early 20th-century naturalists and hunters — people who spent years in the field, observing wildlife up close, and who knew their quarry in detail.

William Thomas Blanford, in The Fauna of British India including Ceylon and Burma (1888–91, pp. 489–493), described the banteng’s distribution as “throughout Burma and the Malay Peninsula extending north to Northern Pegu and Arrakan, and probably to the hill-ranges east of Chittagong.”

Famous naturalist Richard Lydekker, in The Great and Small Game of India, Burma, and Tibet (1900, pp. 56–64), echoed this, noting that the Burmese variety’s range included “the hill-ranges east of Chittagong” and even Manipur, India.

These were not vague guesses; they were based on physical observations and hunting records, many of which were published in the earlier issues of the Journal of Bombay Natural History Society (JBNHS).

Fitz William Pocock and William Thom, in Wild Sports of Burma and Assam (1900, pp. 381–400), perhaps portrayed the most vivid accounts, providing a detailed map of British Upper Burma that placed banteng squarely in regions adjacent to what is now southeast Bangladesh.

Major George Evans, in Big-game Shooting in Upper Burma (1911, pp. 81–120), offered thorough descriptions, describing bantengs’ appearance, habits, and the specific landscapes they frequented. Earlier issues of JBNHS contain numerous similar anecdotes, highlighting a widespread status of the species during that time.

These authors were not confusing banteng with gaur, another species of wild cattle sharing the habitat. They differentiated the two species clearly — noting, for example, that while both can have dark males, the banteng’s overall build, horn shape, and female colouration set it apart.

They specifically called bantengs the Tsaine, a colloquial name of the period, whenever describing an instance.

Finally, Anwaruddin Choudhury’s JBNHS paper in 2020 reinforced these historical records and discussed the possible presence of the species in the Manipur–Myanmar border region.

When memory fades

A tawny-coloured coat is a known feature of the Mainland Southeast Asian subspecies. However, variations in coat colour—from a dark chocolate pelage to the absence of the distinctive whitish rump, an appearance very close to gaurs—were observed by various authors. Due to inadequate data, the actual facts are currently difficult to ascertain. PHOTO: WIKIPEDIA

If the historical literature is so clear, why are bantengs absent from the oral traditions of many Chittagong Hill Tracts communities today? For this, I turn to the work of Choudhury, whose surveys in Manipur in the late 20th and early 21st century revealed something telling.

During his visits in 1988, 1996, and 2001, Choudhury found that younger villagers could readily identify gaurs, but not bantengs. Older residents, however, instantly recognized the banteng — whose lighter tawny coats and white rumps stood out from the darker gaurs — when shown illustrations. In some cases, people recalled seeing them in valleys near the Myanmar border as late as the 1960s and early 1970s. But with no sightings for decades, the knowledge was fading.

It’s not hard to imagine a similar process in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. If bantengs vanished earlier than gaurs — and if younger generations grew up only seeing or hearing about gaurs — then the banteng would quietly slip from cultural memory, its stories blurred or replaced.

Why gaurs survived but bantengs did not

The disappearance of bantengs from Bangladesh, while gaurs persisted, comes down to habitat preferences. Bantengs favour open grass-jungle mosaics and low-lying valleys with scattered trees — landscapes that were far more accessible to hunters. Gaurs, in contrast, are more at home in rugged, hilly forests, which are harder to penetrate and thus offer some refuge from human pressure.

The Chittagong Hill Tracts, despite their name, contain broad valleys and low-lying forested areas that would have suited the banteng well. But these same valleys would have been prime hunting grounds, with little in the way of natural protection from rifles.

In the colonial Upper and Lower Burma, hunting accounts abound.

Both colonial sportsmen and local hunters targeted bantengs for meat and trophies, and often showed preference for relatively flat grassy terrain as ideal sporting ground. Given the species’ preference for a more open landscape, its extinction in Bangladesh may have been swift once firearms became widespread.

Their open-country habits also meant that bantengs were more exposed and predictable in their movements, making them easier targets. With likely smaller and more fragmented populations than gaurs in the region, they would have had little resilience against sustained hunting pressure. Because of the likeness of a riskier habitat, bantengs had an almost legendary wariness and were always considered a prize when approached on foot.

Why denial matters

Extinction is tragic, but it is at least a natural endpoint for a species in a given region. Erasing its history is a different kind of loss — one that undermines both our understanding of biodiversity and our ability to learn from the past.

When respected voices repeat unverified doubts about a species’ presence, they risk replacing documented fact with hearsay. In the case of the banteng, this has meant that an entire generation of conservationists in Bangladesh is exposed to ‘wrong guesses’ believing the species was never here at all.

This matters. Historical baselines shape conservation priorities. If we don’t know what once lived in our forests, we can’t accurately measure what we’ve lost — or set meaningful goals for restoration.

The banteng will not return to Bangladesh. Its habitat is gone, its herds long vanished. But the record should remain straight. The Chittagong Hill Tracts were once part of the banteng’s range, just as they were for gaur, elephants, tigers, and other large mammals. The evidence is in the literature, the maps, and even in the fading memories of elders from neighbouring regions.

If we allow ‘wrong guesses’ to overwrite documented history, we risk repeating the same mistake with other species. Today’s rare, overlooked mammals could be tomorrow’s myth — their absence explained away not as a loss, but as something that was never there to begin with.

Finally, revisiting these historical truths isn’t just academic nitpicking. It’s about respect — for the species, for the people who once lived alongside it, and for the integrity of our conservation work.