The conundrum of English-Medium tutoring

High pay, long hours, and little room to grow: Bangladesh’s English-medium tutoring industry rewards effort but challenges endurance

The conundrum of English-Medium tutoring

High pay, long hours, and little room to grow: Bangladesh’s English-medium tutoring industry rewards effort but challenges endurance

By the time Kazi Farhan Mahi turned 19, he was earning more than many entry-level professionals in Dhaka. He had not planned it that way. Teaching was not something he had set out to do, nor had he imagined it as a long-term path at the time. It began when he was 17, at a moment when continuing his own education depended on his ability to manage money independently.

English-medium education in Bangladesh is expensive, and his family was then going through a financial crisis. With no work experience and still a student himself, tutoring was the only option available. Like many students across different education streams, he turned to private tuition out of necessity.

What began as a temporary solution gradually became something long-term. Mahi started out with home tuition and by assisting teachers at coaching centres. Years later, he is now the Head of Sections, from Middle Years to A Levels, at Reverie School. The distance between those two points appears neat when stated plainly, but the path was far from smooth.

After completing his A Levels, Mahi planned to study abroad. The funding did not come through, and he had to continue his education in Bangladesh. That came with its own complications. “It’s tough to get into public universities from an English-medium background,” he says. “So I had to look at private universities. Again, I needed money to continue my education, because private universities cost more.”

By then, tutoring was already part of his life. One of his former teachers suggested that he apply to schools. “I thought if I joined a school, I’d be able to connect with more students,” he said.

He later began teaching at a school. Since then, his life has been split between schools, private tuition and coaching centres. He does not regret that choice. “I really enjoy teaching,” he said. “When I interact with my students and see their achievements, it gives a different kind of joy.” For him, the work has remained meaningful. For others, it does not last as long.

Nylah Shah, a former O/A Level English teacher, entered the same world for similar reasons. She began tutoring at the age of fifteen. “I was a kid myself when I started tutoring,” she says. After a few years, she began teaching at a school.

Between 2015 and 2020, she worked at four English-medium schools. Alongside this, she took home tuition and taught at private coaching centres in Dhanmondi, and later in Gulshan.

“What stayed constant through all those years was coaching,” she said. “When you teach in a school, students get to know you. They trust you with their education.” That trust travels easily from classrooms to coaching centres and into private homes. After 2020, Nylah shifted to online teaching. In early 2025, she left the profession altogether, despite the income.

Taken together, stories like Mahi’s and Nylah’s point to a much larger structure that runs informally alongside formal education. A vast private tuition and coaching culture has grown around English-medium education, fuelled by exam pressure, parental anxiety and the limitations of schools themselves. From the outside, it can be difficult to see. There are no official figures, no reliable data. But the scale becomes apparent once you look at the number of students involved and the fees being charged.

According to Mahi, income in this space depends entirely on how much physical and mental effort someone is willing to put in. “You can earn anywhere from Tk90,000 to Tk10 or 12 lakh per month. I even know people running coaching centres whose monthly income is Tk30 to 32 lakh,” he said. Since this is not a fixed profession with a formal salary structure, it is closer to piecework, where time, energy and reputation translate directly into cash.

Several factors have contributed to the growth of this system. One of these is the flexibility of the exam registration process. English-medium students can register for O and A Level exams either through schools or privately. For many, that choice becomes strategic.

Dhrupadi Auditi, an A Level student, explains how this works in practice. “After a certain stage at English-medium schools, apart from the really good, well-known ones, the education isn’t that strong,” she said. Being registered through a school still matters, especially as universities tend to prioritise institutional candidates. But cost and flexibility often push students in another direction. “Some students prefer sitting independently for exams,” she said. “Those who attend school regularly also get tuition and coaching, but students who sit privately definitely rely more on private tutors and informal coaching centres. I myself, for my O Level exams, did not attend any school or formal institution, but for the exams I registered under Academia School.”

Exam registration fees are already high. When those costs are added to school tuition, along with coaching and private tutoring, education becomes unaffordable for many families. “If schools can’t meet the required needs of students, why wouldn’t they seek private tuition?” Dhrupadi asks. “Nobody wants to sit and retake again and again, paying so much money.”

This demand feeds a parallel system. In most cases, tutors enter it for financial reasons—covering education costs, becoming independent, or supporting their family. There are exceptions. “I have a few students who tutor just for the process,” Mahi said. “They enjoy teaching.” But enjoyment alone rarely sustains the work.

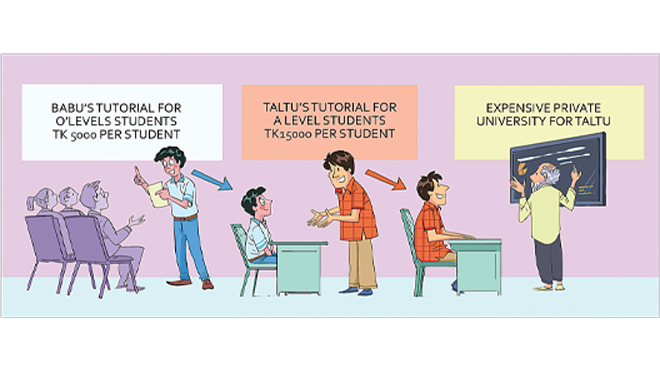

Usually, it starts with one-on-one tuition. As demand grows, tutors move into coaching. Often, a few teachers rent a space together—one or two rooms, sometimes an entire floor—and divide it based on availability and affordability. That is how many coaching centres begin. To keep the cycle going, tutors also try to work in schools. Schools offer visibility. Coaching centres offer volume and income. Home tuition offers flexibility. Most juggle all three.

Fees vary sharply by location. English-medium tuition is already more expensive than other systems, for reasons that include international curricula and specialised instruction. Even within this tuition culture, there are differences. “A private tuition that costs eight to ten thousand in the Dhanmondi area becomes fifteen to eighteen thousand in Gulshan,” Mahi said. Coaching fees shift in the same way, shaped by neighbourhoods and the economic background of families.

The money, of course, is good. The cost, however, can be exhausting. Balancing school jobs, coaching classes, home tuition and personal studies drains people quickly—especially when they start young. “For a long time, I was doing everything at once,” Nylah said. “I was teaching in a school, teaching at a coaching centre, and I was a student myself. At one point I thought, enough. I need rest.”

Beyond fatigue, there is also stagnation. “When you start, you learn a lot,” she said. “But after a few years, you realise there isn’t much scope to grow. I was doing the same thing over and over again. I was earning well, but I felt stuck. It didn’t require learning new things anymore. I felt like I had more to offer through my work than repeating the same lessons.”

Mahi sees the limits too. “Your income depends on how much physical and mental effort you can give,” he said. “After 35 or 40, you can’t continue the way you did in your 20s. That’s why many people eventually switch careers.” Social pressure plays a role as well. Traditional jobs still carry a certain legitimacy, even when they pay less.

But switching is not that simple. Entry-level formal jobs rarely offer high pay. For someone used to earning three or four lakh a month, stepping into a position that pays one lakh, or less, requires sacrifice. Lifestyle, responsibilities and expectations all come into question.

In the end, it comes down to priorities. Teachers like Mahi, who still enjoy the work and are willing to continue, stay. Others, like Nylah, reach a point where the cost outweighs the return and choose to leave.