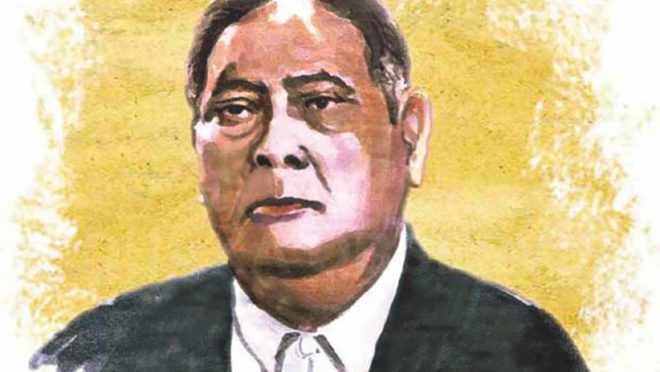

AK Fazlul Huq: The Sher that roared for Bengal

AK Fazlul Huq: The Sher that roared for Bengal

Throughout history, there are certain politicians who change its course—whether for better or worse is a different discussion—but no doubt should persist that they are a unique breed who can both entice the people with their personalities and play the game behind the scenes with incredible precision and integrity.

On 26 October 1873, the Indian subcontinent saw the birth of one such extraordinary figure whose politics would result in the creation of two independent nations, Pakistan and consequently India, and after a while, his own Bengal nationalistic aspirations would lay the groundwork for another independent nation called Bangladesh.

We, as Bangladeshis, often do not know the full history of our predecessors. Whether it be intentional or due to a lack of responsibility, the average person in Bangladesh today only knows AK Fazlul Huq as Bengal’s first Premier but can hardly explain how a Bengali lawyer born in Barisal came to simultaneously become the President of the All India Muslim League and the General Secretary of the Indian National Congress.

Early life

As a young man, it was evident from the start that Fazlul Huq was equipped with all the necessary tools to become one of a kind. His family was among the few highly educated families in Saturia, Bakerganj, and he was homeschooled at first, learning Arabic and Persian. After that, he went to Barisal Zilla School and then excelled at Presidency College, earning a triple bachelor’s degree in 1894. He completed his master’s in mathematics (1896) and a law degree (1897), becoming one of the subcontinent’s first Muslim lawyers.

This illustrious educational achievement meant that Bengal was full of mythical and mystical stories highlighting the brilliance of Fazlul Huq. One common story was that he would read the pages of a book once and memorise it instantly, then tear the pages apart, as there was no need of it because he had memorised it so well.

An obvious exaggeration. However, his achievement in the early 19th century was remarkable, and in today’s age, graduating with a triple bachelor’s is unheard of and may be impossible to achieve.

Political career

Born into wealth, Huq benefited from a good education which his family could afford, but unlike other prominent Muslim families, he did not sell out by becoming an Anglophile. The glitz and glamour of aristocratic life could not detach Huq from the plight of the Bengal Muslims.

No wonder why he, an educated lawyer from Calcutta University, started to gain popularity for his fiery tone against the elite. While his speeches inspired thousands across the fields under feudal lordships, his actions frightened the very Bengali elite he was born among.

For an open-minded individual such as Huq, a life in politics was inevitable. Being a firsthand witness to the plight of the Bengali lower castes, he joined the Bengal Provincial Muslim League in 1906 and became its secretary in 1913. Within just three years, in 1916, he became the president of the All India Muslim League—a title later held by Nawabjada Liaquat Ali Khan and Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Along with the Muslim struggle, as an undisputed leader of Bengal, he also held the post of General Secretary of the Indian National Congress (1916–1918).

In the first provincial general elections held in 1937, Huq, with his Krishak Praja Party, won 36 seats in the Bengal Legislative Assembly against 37 of the Muslim League. It was the third-largest party after the Congress and the Muslim League.

He went on to form a coalition government and became Bengal’s first elected premier. In 1940, Huq led the Bengal Muslim League contingent and reached Lahore on 22 March. The famed Lahore Resolution, where the All India Muslim League demanded a separate nation for the Muslims of India, was put forth by Huq and the Punjab Premier Hayat Khan.

This Lahore Resolution can be mentioned as the building block for what was to become Pakistan, and as the representative of Bengal, it was Huq who emphasised the need for Bengal to be included as part of Pakistan as its eastern section.

Huq, throughout his political career, always played the leading role and never the compromiser. When, on 25 August 1941, Jinnah called upon all the premiers to step down from the National Defence Commission in protest against the British government for not consulting the AIML before joining World War II, none but Fazlul Huq defied Jinnah.

While all the leaders of the Provincial Muslim Leagues danced to the tune of Jinnah’s orders, there was Huq, who stood defiant—not just for the sake of disagreement, but for the interests of his own constituency, Bengal. Jinnah said that Mr Fazlul Huq met him and had promised to write to him. Outside the residence of Mr Jinnah, Mr Fazlul Huq told the press, “I will not submit to Hitlerite methods. Let the League expel me. My position in the Bengal Assembly is unassailable.”

Jinnah was forced to bypass Fazlul Huq and influence H.S. Suhrawardy, Sir Nazimuddin, and the Nawab Bahadur of Dacca (Dhaka) to form a new working committee of the Muslim League and argue for Muslim unity under that banner—a banner built upon Huq’s political prowess which had led to the election dominance of 1937.

After partition, Jinnah’s fate would come to haunt him once more. On the eve of the 1954 election, it was quite clear that his Muslim League, devoid of H.S. Suhrawardy and Bhashani, would not be able to gain the Bengali vote any longer.

The people of Bengal rejected the Nawabs and Sirs sitting in their bungalows in Dhaka and elected to the provincial assembly the Juktofront, a coalition led by Fazlul Huq, H.S. Suhrawardy, and Bhashani.

The Juktofront’s 21 points are argued by historians to be the first document aimed at gaining full provincial autonomy for East Bengal and were the manifesto that ensured that out of the 300 seats, the Juktofront would win 230 of them, later becoming the foundation upon which Sheikh Mujibor Rahman famously issued his six points.

However, as in all instances, the Pakistani elites, still bearing the rotten stench of feudalism, failed to comply with the people’s verdict, and on 27 October 1958, General Ayub Khan deposed Huq and his democratically elected government. Soon after his dismissal, the statesman known as Sher-e-Bangla (the Lion of Bengal) died in 1962 aged 88.

The legacy

The Sher lived up to his namesake—never undeterred from his sense of right and wrong, always representing the poor even to his detriment. This was an enduring legacy.

It is a shame that such a pioneer of political emancipation is not remembered with the respect he deserves.

Pakistan branded him as a traitor, as he, on multiple occasions, clashed with the “all-knowing” Quaid-e-Azam, and later, with his government’s 21 points, personified the plight of the East Pakistanis.

And in Bangladesh, he is little more than a trivia question, limited to the myths of his educational achievements, but not remembered as someone who gladly showed the proverbial middle finger to the British by not accepting knighthood, and who stood up to Jinnah’s cult known as the Muslim League—which was once Huq’s own creation—but he did not hesitate for a second to denounce it when he saw fit.