America’s original storyteller: Remembering Mark Twain on his 189th birthday

America’s original storyteller: Remembering Mark Twain on his 189th birthday

A Childhood by the Mississippi river

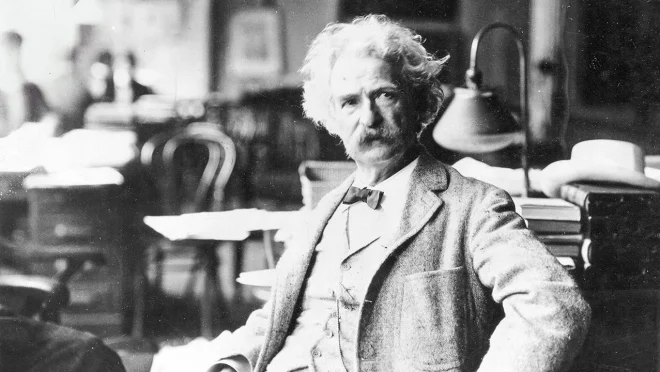

Mark Twain, born Samuel Langhorne Clemens, remains one of the most recognisable figures in world literature. The white suit, the shock of unruly hair, the dry humour and the pointed squint all helped turn him into an American icon. But behind that familiar image was a boy shaped by a river.

Twain was born on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri and grew up beside the Mississippi, a restless landscape that carried stories, danger and possibility in equal measure. The river, with its shifting currents and colourful characters, fed his imagination long before the world knew him as a writer.

His early life swung between roles: printer’s apprentice, steamboat pilot, miner, journalist, and roving observer. These experiences gifted him not only material but a rare instinct—the ability to capture the rhythms of ordinary speech.

At a time when American literature aspired to sound polished and European, Twain wrote with the raw, unfiltered cadence of the frontier. It was a quiet but transformative departure, one that helped shape a new, distinctly American voice in fiction.

Inventor, experimenter, early adopter

Twain’s influence extended beyond the page. He was unusually open to new ideas and technologies, even when he joked about them. One of his most surprising legacies is his early embrace of the typewriter. He grumbled about its clattering keys and once called it a “plague,” yet he became the first author to submit a fully typewritten manuscript for publication.

This small but significant shift, likely for Life on the Mississippi, signalled a turning point in literary history. It marked the beginning of the modern writer’s relationship with machines. Twain’s curiosity pushed him toward inventions and bold publishing ventures. Many of these experiments failed, often spectacularly, but they reflected his restless need to move forward.

Fame and the cost of ambition

By the late 19th century, Twain was no longer just a writer. He was America’s first true literary celebrity. His lecture tours drew crowds worldwide; his wit earned him invitations to dine with presidents and spar with intellectuals. People didn’t simply read Twain—they watched him, quoted him and followed his travels.

But fame did not shield him from hardship. Twain’s financial life was riddled with disastrous investments, especially in new technologies that never succeeded. When bankruptcy loomed, he set out on gruelling lecture circuits across Europe to repay his debts—performances that brought cheers from audiences but left him emotionally drained.

His personal life was equally marked by sorrow. The deaths of his wife and three of his four children cast long shadows over his later years. The humour stayed, but the edges grew sharper. His writing became more introspective, sometimes more bitter, reflecting a deepening disillusionment with humanity.

A man of dazzling brilliance and deep contradictions

Modern biographers present Twain not as a flawless hero, but as a man filled with contradictions. He questioned racism, yet shared in the prejudices of his era. He criticised imperialism while struggling with the privileges he himself enjoyed. He celebrated the innocence of childhood, yet his close friendships with young girls he fondly called his “angel-fish” remain subjects of discomfort and debate today.

These complexities do not diminish his legacy, but they complicate it, reminding readers that literary giants are human too. Twain’s life, in many ways, mirrors the uneasy history of America: brilliant, ambitious, creative, but far from uncomplicated.

Why Twain still matters today

More than a century after his death, Twain’s voice refuses to fade. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn remains central to American literature not only for its humour and adventure, but for its unflinching examination of the country’s deepest contradictions—freedom and enslavement, innocence and cruelty, idealism and reality.

Twain’s use of vernacular speech paved the way for modern storytelling. His experiments with narrative form and technology show a willingness to take risks that still feels contemporary. And his personal struggles—financial, emotional and philosophical—offer a reminder that creativity often emerges from uncertainty.

For young readers today, Twain’s relevance lies not only in his legacy but in his restlessness. He represents curiosity, self-questioning and the courage to challenge social norms. His life suggests that great ideas are seldom neat, and that doubt and exploration are essential to understanding the world.

Returning to Twain on his birthday

Mark Twain once joked that “reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” More than a hundred years later, his words hold true. His stories continue to move across generations, oceans and cultures—sometimes comforting, sometimes provoking, always enduring.

On his 189th birthday, remembering Twain means remembering a writer who refused to stand still. It means returning to a mind that questioned everything, from politics to religion to human nature itself. Most importantly, it means recognising that his contradictions make him not less relevant, but more real.

The river that shaped him was long, unruly and full of surprises. So was he. And that is why Mark Twain still matters today.