Exploring the Bangladeshi horror genre

Exploring the Bangladeshi horror genre

For many of us, growing up as an avid fan of the horror genre usually meant an obsession with Hollywood jumpscares and gory Turkish horror franchises; with the occasional Bollywood classic like 1920 being thrown in the mix every once in a while to spice things up (Thanks, Sony Max!).

However, podcasts like Bhoot FM on Radio Foorti or Dor on ABC Radio were nothing short of a cultural phenomenon in their own time–which indicates how badly we still yearn for quality stories and works in the Bangladeshi horror genre as a whole. We have zero shortage of mythologies, folklore, urban legends, and local paranormal phenomena of our own; and an active effort to explore these with a creative lens can introduce a whole new horizon for films, tv shows, and many more.

We may assume that the Bangladeshi horror genre has yet to achieve a commendable standard in terms of atmospheric audiovisual storytelling beyond predictable tropes; but over the years there have actually been some remarkable works that deserve recognition. Previously they were produced in the form of TV dramas and telefilms, but the rise of OTT platforms and independent filmmaking has given the genre a whole new dimension.

To begin with, Humayun Ahmed’s Odekha Bhubon was a seminal work in the 90s horror genre in Bangladesh. Based on a series of stories he had penned previously, this series of 8 different TV dramas that aired in 1999 was certainly ahead of its time. Bonur Golpo, Churi, Dwitiyo Jon, Mrittur Opare, and Agun Mojid are some of the best stories to come out of this series.

Compared to contemporary standards, you might expect a Bangladeshi horror drama from the 90s to feel irrelevant or even comic owing to its lacklustre CGI. While it is true that these don’t feature what we now would consider quality horror cinematography and editing; the sheer depth of the storytelling, as well as the masterful blend of the supernatural and psychological horror, makes this series an absolute standout even 26 years later.

The next severely underrated title has to be Aalo, a telefilm created by Taneem Rahman Angshu, who you may better recognise as the director of No Dorai (2019). There is surprisingly little to no information available about this anywhere on the internet, despite a stellar cast featuring Aupee Karim, Tamalika Karmakar, and even Partha Barua. You can only watch it by searching for Aalo Bangla Telefilm on YouTube.

Aalo follows the story of a newly pregnant married couple whose lives are turned upside down after the arrival of Rabeya, a new househelp, into their home. It grapples with themes of black magic, family, loss, and how secrets can haunt us our whole lives.

Despite very little use of typical jumpscares, the atmospheric storytelling, terrific acting, and twisted plotline is truly worth a watch. It’s hard to pinpoint the release timeline for this telefilm but given the nuances within the film, it may have been released sometime in the early 2010s. The quality of this telefilm is such that you can tell it would’ve been an instant classic if released on an OTT platform in the present day.

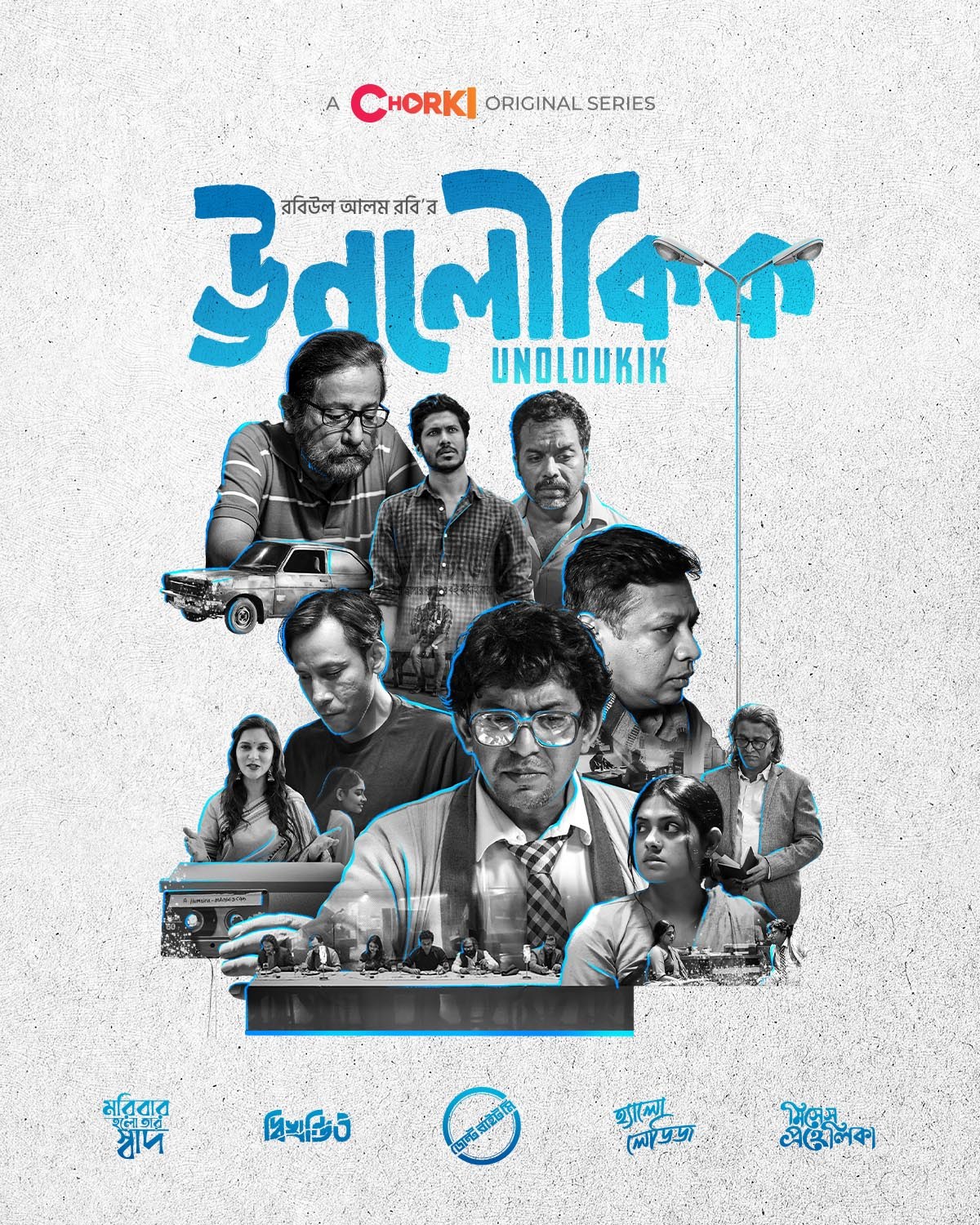

Speaking of OTT platforms, contemporary creations like Nuhash Humayun’s Pett Kata Shaw and Dui Shaw, as well as Unoloukik by Shibabrata Barman and Robiul Alam Robi on Chorki also deserve a mention.

The Pett Kata Shaw series (which now has a second season, Dui Shaw) more or less took the internet by storm upon its release in 2022; paying an ode to some definitive local folklore and beliefs we have been encultured into our whole lives. The short series not only brought to life beliefs such as – Jinns love eating mishti, or that you mustn’t go out with your long hair untied at night; it put a psychological twist onto these beloved stories by exposing some of the deepest, darkest sides of what it is to be human.

The second season, Dui Shaw, follows closely through the same theme but in a different manner; with an even sharper focus onto the ‘humane’ part. Some of the best stories to come out of this series include Mishti Kichu, Loke Bole, Antara, and Bhagya Bhalo; although all of them were received well by the audience.

The series Unoloukik may not be straight up horror-based, but its psychoanalytic approach and otherworldly, mysterious nuances demand a special mention. The dark satire and genre bending combination of reality and magical realism in Unoloukik is almost reminiscent of what you may feel as an audience watching Black Mirror, where everything seems downright strange until you slowly begin to realise how terrifyingly familiar it is to our embodied experiences in a post-postmodern world. Even if horror isn’t your cup of tea but everything beyond realism interests you, each and every episode of Unoloukik is a must watch.

Besides the aforementioned creations, there is also Debi(2018)–a beloved supernatural thriller in both its book and film form, and Moshari (2022), an award winning unique take on creature horror in a dystopian setting that’s available for streaming on Vimeo. Additionally, there are many Bangladeshi independent filmmakers on Youtube regularly making horror films that feature many familiar faces of the industry.

Although most of them fail to go beyond stereotypical predictable elements; the production quality is gradually improving and at the end of the day, a consistent effort is an important effort nonetheless. Overall, though commercially successful or critically acclaimed works of Bangladeshi horror are few and far between; it’s undeniable that there has been a slow, yet visible evolution in this genre over the last few decades.

It may sound far fetched, but horror is the kind of genre that shouldn’t be confined to physical gore, jumpscares, and superficial themes because the unknown and otherworldly are often the realms where we find the truest reflections of the human psyche, and even our sociocultural realities.

Prejudice, superstitions, and myths are simply stories that precede our existence and our contemporary realities and logic, and there has to be a reason why they have endured for generations. While those reasons may be a matter of opinion, there is no doubt that the horror genre is a powerful tool of storytelling that can operate heavily on metaphors and countless possibilities of interpretation. In a global, and most importantly local climate of incessant censorship and political turbulence, shouldn’t that be considered an essential loophole for the creatives?