Bhutto and Pakistan through Bangali eyes: What ‘If I Am Assassinated’ tells us

Bhutto and Pakistan through Bangali eyes: What ‘If I Am Assassinated’ tells us

In the history of the sub-continent, there are very few who hold such a compelling comeuppance as the former President of Pakistan, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. As one of the icons of Pakistani politics, knowing about him not only will give the reader an outlook into the domestic politics of Pakistan but also will provide the geo-political intermingling of political hierarchies in India and Bangladesh. Therefore, learning about this iconic character is very relevant for any Bangladeshi student of history. His memoir named If I am Assassinated gives such an opportunity to know about his history and inner workings of politics in the subcontinent.

Backdrop

This memoir was written by Bhutto when he was accused of murder and was relegated to a death cell in Rawalpindi. The conditions were not suited for a man of his stature. A man of aristocratic upbringing, the Oxford grad and former professor of UC Berkeley jumped at the first opportunity to enter Pakistani politics in 1956 by joining as the commerce minister in the Ayub government; little did he know that at the prime age of 51, he would see himself as the President of Pakistan, the author of the Pakistani nuclear story, and even a convicted murderer.

The book was initially smuggled out in pieces by his personal dentist who would visit Mr. Bhutto once a month. The book is his personal hand-written account in response to General Zia-ul-Haq’s two white papers, which was published with an aim to slandering Bhutto and accusing him of fixing the 1977 elections.

The facts mentioned in the white papers may be hard to comprehend or judge for a Bangladeshi reader. However, the fascination of the book appears not in its factual statements rather it originates from the ambiance of expressions of the arrogant, ambitious and the ever defiant Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

Journey towards becoming the first civilian martial law administrator

After 16 December 1971, Pakistan was in chaos. Being humiliated, economically destroyed, and morally distorted, the military rule of Yahya seemed to be at its end. Bhutto, however, was as ready as ever. Fresh out of his grandiose speech at the UN Security Council, Bhutto went to the White House to get the blessings of the U.S. Soon he returned to the war-torned Pakistan and on 20 December 1971, Yahya surrendered power and made Bhutto the first ever ‘civilian’ martial law administrator. A weird title, but as it will soon be obvious, that for Pakistani politics, no unconventional approach is ever too unconventional.

In his book, Bhutto clearly portrayed himself as the savior of Pakistan and he displayed a strong disdain for the military. He provided his reasoning for why Bangladesh wanted separation. As a Bangladeshi reader, it might be a surprising notion to see Bhutto outright acknowledge the genocide committed by the Pakistani Army which is legitimized by the Hamidoor Rahman Commission that he helped publish. More importantly, a weakened Bhutto would shoulder no responsibility for the 1971 war, as he so confidently declared his acceptance of ‘most’ of the six point demands of the Awami League. One could guess that he shared a keen but mild appreciation for Sheikh Mujibor Rahman as he successfully negotiated the release of 193 prisoners of war as well as court marshall certain generals for losing the war and violating ‘direct’ commands. Tiger Niyaji was one of those generals as the famous ‘feline’ failed to keep Pakistan in one piece.

A false sense of superiority For a man, who could not win the 1970 elections and had achieved power despite it, he babbled on and on about the importance of elections in this book. The false bravado he bestowed upon himself was quite evident. He saw the rise of the PPP and its leader as the new representation of a socialist revolution in Pakistan.

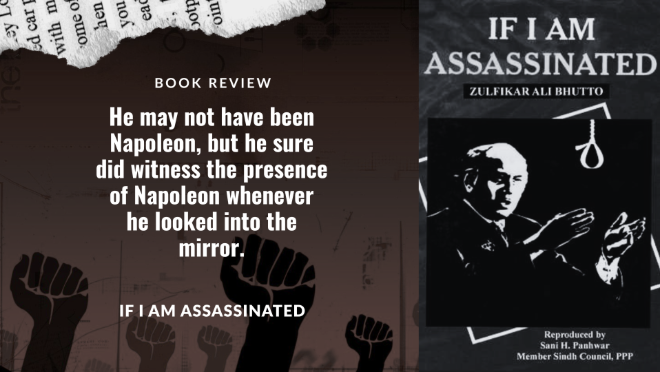

He entertains the reader by expressing his humility in one paragraph, but in the next balances it out with the blind fanaticism of himself by comparing himself to Napoleon. Not the emperor but the liberator of the French, as he saw Napoleon to be. His love for certain historical figures was quite remarkable, as he picked and chose certain traits and quietly ignored the questionable ones. Certain dictators such as Charles D’Gaul and Gaddafi were among his favourites. His arrogance was often balanced by the raw emotions throughout this tough predicament. He, after all, was confined to a death cell and about to meet his fate.

He unexpectedly broke down emotionally when he would mention his beloved wife and children. He was a proud husband and father. It seems, he was quite close with his daughter, Benzir, as well, who would follow in her father’s footsteps and become the PM in the future.

Although the book is littered with facts and notes, its emotion is not lost. As it is expected, such a highly educated and accomplished personality wrote his memoir quite eloquently, and it showed in every word whenever he would express his love for his family and even the average Pakistani.

Pakistan in the eyes of Bhutto His grand vision for Pakistan was clearly outlined in this book. It was he who quietly organized the inner workings of the Pakistan Atomic Commission and used the French to help build the nuclear power plant in Pakistan. His conversation with Henry Kissinger suggests that the U.S. was not happy with this decision and he, multiple times, alluded that the U.S. embassy was conspiring against him in order to delay any development in enriching Uranium.

Henry Kissinger famously told Bhutto, “don’t insult our intelligence by saying this nuclear power plant will only be used for producing electricity”. The answer in reply is precisely the reason you should read this book because it will show the truest character of a seasoned politician who is unwilling to sacrifice his morale no matter how many holes his arguments might possess.

The relevance in today’s geopolitics Pakistan today, by all metrics, is shaping out to be a failed state. Time and time again, the army stood in its way with the delusion of saving the country while burying it under obscurity.

The consequences we see today were all outlined in Bhutto’s book. In a death cell, awaiting for the verdict that will eventually take his life, he predicted the end of polity in Pakistan if the ‘coup-gemony’ persists.

In his short life of 51 years, this grandiose character had seen and done it all. The elite of the elite lived up to all the expectations one could have. He became one of the youngest ministers in the history of the world at the age of 29. He made himself the subject of love among the masses, while politicking his way to ultimate power.

So one should read his book not for the propaganda it spits out, rather one should read it to witness history as an unbiased observer.

He may not have been Napoleon, but he sure did witness the presence of Napoleon whenever he looked into the mirror.