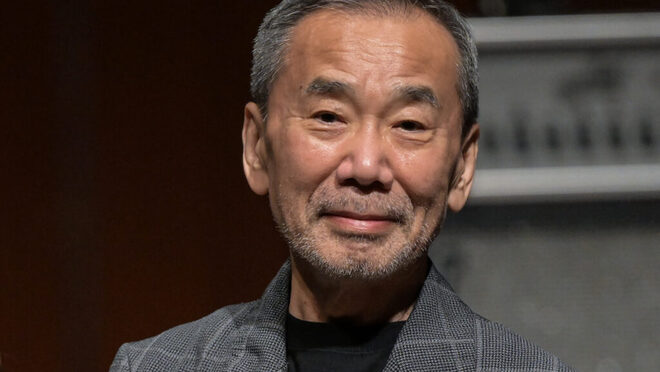

The comfort of being unsettled: Reading Murakami

Walk into any bookstore in Neelkhet or a café in Gulshan, and you’ll spot them everywhere: Murakami novels stacked on shelves, tucked into backpacks, photographed for Instagram stories.

The comfort of being unsettled: Reading Murakami

Walk into any bookstore in Neelkhet or a café in Gulshan, and you’ll spot them everywhere: Murakami novels stacked on shelves, tucked into backpacks, photographed for Instagram stories.

His books get dog-eared by university students, annotated in margins, and passed between friends. As 12 January marks the writer’s birthday, let’s take a moment to consider why young people read him so intensely, and what makes his writing so compelling once you learn to overlook the frustrating parts.

An epiphany in the bleachers

In April 1978, Murakami was sitting in the bleachers at Jingu Stadium in Tokyo, watching the Yakult Swallows play the Hiroshima Carp. He was 29, running a jazz bar called Peter Cat, drinking beer like any other evening.

As he witnessed a clean double hit by American player Dave Hilton echoing through the field, it stirred something unexpected in him. In that instant, he felt a warm certainty that he could write a novel, and that night he began working on Hear the Wind Sing, his first book. Years later, Norwegian Wood became massive in Japan.

By the time his work reached young readers in Bangladesh, he was already legendary.

His novels are strange on purpose, deliberately odd in their construction. His characters are usually isolated, searching for something they can’t quite name or articulate.

A woman falls asleep for years. A man finds another person living quietly in his closet. These stories don’t offer answers or resolutions. They explore what’s hidden beneath the surface, the gap between what we show the world and what we actually feel inside.

In a crowded city like Dhaka, where you’re surrounded by millions of people yet somehow completely alone, this resonates deeply. His words capture that specific modern loneliness perfectly.

Looking for meaning in parallel lives

Murakami writes constantly about parallel realities, about another side where different versions of life exist simultaneously. It’s his way of exploring what meaning actually is. He is influenced by existentialist ideas, the sense that life doesn’t come with built-in meaning, that we have to search for it ourselves.

His characters wander around, as they look for something authentic in a world that feels hollow. This appeals to young people trying to figure out who they really are.

For Bangladeshi readers, encountering Murakami through English translations is crucial. Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel translated Murakami into English, and this matters far more than people realise.

Murakami’s use of jazz, Western pop, and everyday objects shapes his emotional atmosphere and helps readers ease into difficult themes without feeling overwhelmed. A bad translation would have killed everything stone dead.

But they understood his minimalist style, his quiet sentences, what he deliberately leaves unsaid between the words. They made him genuinely readable for English speakers. The translation itself carries a kind of music that makes literary fiction feel accessible to people who might never have tried it otherwise.

Women seen from afar

This is where Murakami becomes harder to defend. His female characters are often written with much less depth than his male ones. They usually exist in relation to the male narrator, appearing as someone to love, lose, or remember, rather than as full people with their own inner lives.

In Norwegian Wood, women are often described through beauty and fragility, while Kafka on the Shore includes scenes that many readers find uncomfortable, especially involving young girls. Some readers say this is deliberate, showing how Murakami’s male characters fail to truly understand women. That may be true, but it does not change how repetitive the pattern feels. For many readers, especially women, this distance becomes frustrating and limiting.

Existing in the in-between

Despite his real flaws, Murakami genuinely matters to young readers. His books allow one to feel lost and confused without needing to fix it immediately. They suggest that loneliness isn’t a problem but something worth examining carefully.

His words are strange, but they feel honest and true. In a country like ours, where family expectations and social pressure can be overwhelming, his characters’ quiet disconnection feels like recognition to the audience. Murakami understands what it’s like to be present in your own life but not fully there, which caught the attention of many.

The writers who came after him

Murakami didn’t arrive fully formed from nowhere. He was influenced by Western writers like Kurt Vonnegut and Truman Capote. But his success opened doors for other writers everywhere. Young authors started experimenting with similar approaches, mixing surrealism with emotional minimalism.

They created strange worlds that somehow feel true and honest. Writers across Asia, including some in Bangladesh, absorbed his approach and made it their own. The influence spread quietly through literary communities, changing how people thought about what fiction could do.

You may love reading Murakami at some point in your life, and find outgrowing him in other times, yet keep coming back for the moments that make you feel seen. Love him or get frustrated with him, the lingering spell of Murakami remains strangely hard to ignore.