World Keffiyeh Day: How Bangladeshi youth embraced the Palestinian headscarf

World Keffiyeh Day: How Bangladeshi youth embraced the Palestinian headscarf

11 May is World Keffiyeh Day. Once a scarf for shielding against sun and sand, the keffiyeh has evolved into a global symbol of Palestinian identity and defiance.

Also known as the kufiya, shemagh or hatta in Arabic, the keffiyeh’s roots trace back to Mesopotamia, or modern-day Iraq, as early as 3100 BC. In Palestine, it was originally worn by rural farmers, or fellahin, to protect their heads from heat and dust.

And now, people from all across the world wear keffiyeh to express solidarity with Palestine. The PLO leader Yasser Arafat popularised the keffiyeh on a global level. From Nelson Mandela to celebrities like Bella Hadid, David Beckham, and Kanye West—all wore keffiyeh to stand with the Palestinian cause.

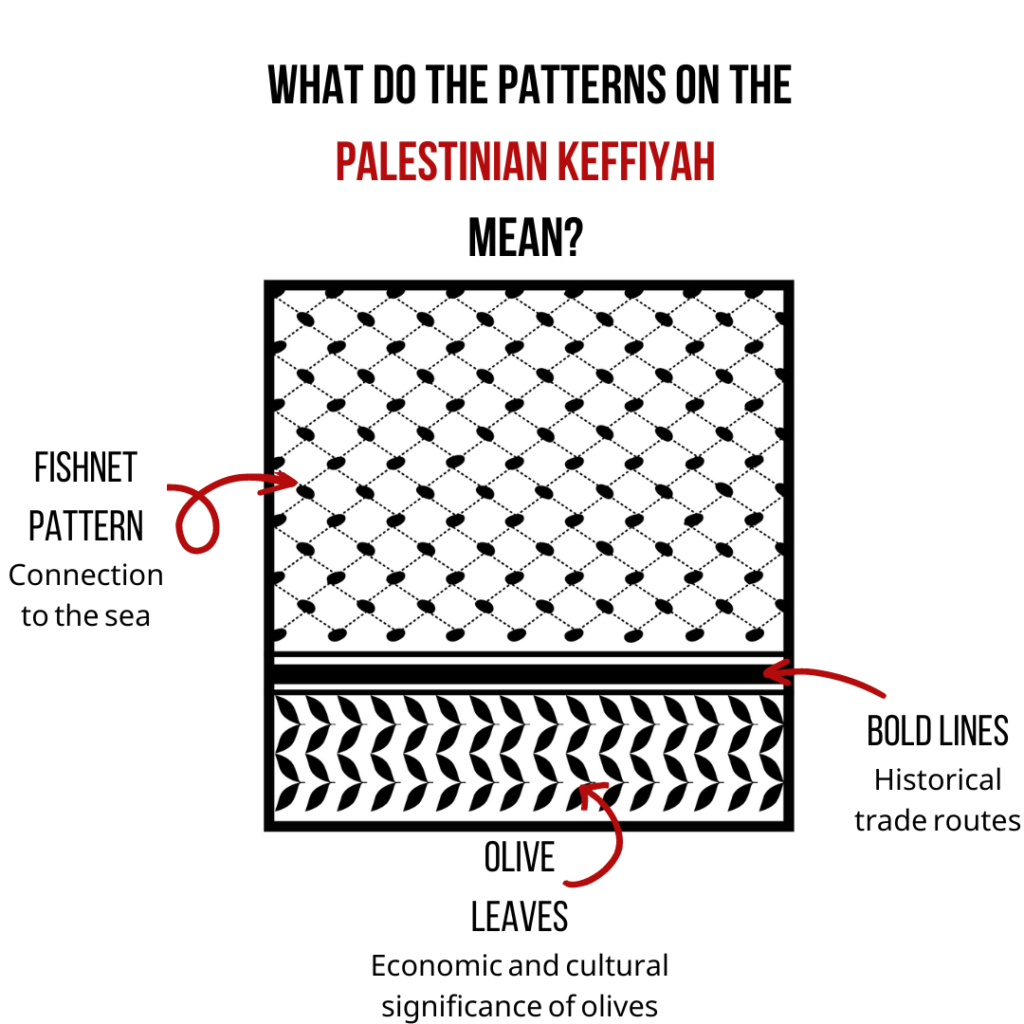

The scarf’s patterns—although apocryphal—have also gained new interpretations. Some say the fishnet design symbolises connection to the sea. Others, like Palestinian poet Fargo Tbakhi, see barbed wire in its shape. Still others say it represents unity—an interconnected net of individuals bound together, stronger as one.

In Bangladesh, where generations of elderly men and religious scholars have long worn the patterned cloth, Gen Z is reclaiming it—not as tradition, but as an act of protest and solidarity.

Dr Shahidul Alam, celebrated photojournalist and Ekushey Padak laureate, has long worn the keffiyeh as part of his public identity. “Worn across the Arab world, the keffiyeh represents heritage,” he reflects. “But in Palestine, especially since the 1930s Arab Revolt and figures like Yasser Arafat, it came to signify national identity and resistance against occupation. I started wearing it in 2016 when Israel was attacking Gaza. That attack now pales in comparison to the genocide we’re witnessing today.”

Dr Alam think the keffiyeh has become, and rightfully so, an icon of the Palestinian identity itself, “As a symbol of resistance and identity, the keffiyeh became a hallmark of Palestinian identity during British colonial rule and Zionist settlement. Its adoption by Palestinian fighters made it a symbol of defiance. In the 1960s and 1970s, leaders like Yasser Arafat consistently wore the keffiyeh, often draped to resemble the map of Palestine, embedding it in the global image of the Palestinian liberation movement. This made it instantly recognisable as a marker of the struggle against occupation. During the First and Second Intifadas (1987–1993, 2000–2005), the keffiyeh gained prominence among international activists. Its use in protests, from Europe to North America, visually linked global solidarity movements to Palestine, amplifying awareness of issues like displacement, occupation, and human rights abuses.”

In Dr Alam’s telling, the keffiyeh isn’t a passive relic. It’s an active voice. He wore it while addressing the United Nations. He wore it at the Royal Festival Hall in London when receiving an honorary doctorate—one he later returned in protest of the Chancellor’s Zionist ties. And he wore it while accepting the Ekushey Padak. “I take every opportunity to remind people of the Palestinian struggle,” he says. “The keffiyeh makes it visible. It communicates resistance without needing words.”

The Palestinian keffiyeh now speaks for all the oppressed around every corner on earth. “The keffiyeh has indeed evolved into a near-universal symbol for oppressed people in many contexts. Its journey from a regional garment to a global emblem of resistance reflects its adoption across diverse struggles, but its primary association with the Palestinian cause remains central”, Dr Alam says.

It is precisely this sentiment that resonates with Bangladeshi youth. During the July uprising, the sight of young people wrapped in keffiyehs, waving Palestinian flags, created a powerful tableau. For many, the parallels were unmistakable. A people demanding dignity, justice, and self-determination, standing in solidarity with another doing the same. The shared struggle has only deepened the brotherhood between Palestine and Bangladesh.

Dr Alam interprets this moment as a powerful convergence of histories. “The appearance of keffiyehs during the July Uprising, is a striking example of how symbols of one struggle can be adopted to amplify another. This draws on the keffiyeh’s established role as a symbol of resistance, the historical and emotional ties between Bangladesh and Palestine, and the specific context of the uprising. Protesters saw similarities between their fight against a government accused of electoral rigging, media censorship, and human rights abuses and Palestine’s resistance to occupation and state violence.”

For a country like Bangladesh, whose own independence was forged in blood and courage, the emotional bridge to Palestine is not difficult to cross. And Dr Alam believes the empathy is rooted in shared pain—and a deep yearning for liberation, “The courage of Palestinians facing occupation was seen as a model for their own defiance against Hasina’s regime, which they viewed as tyrannical. Waving Palestinian flags and wearing keffiyehs was a way to invoke this shared spirit of resistance, framing their movement as part of a global fight for justice.”

“It’s a symbol of resistance for Palestinians—and for others, a powerful expression of solidarity,” says Ariful Hasan Shuvo, a journalist in Dhaka. “I wear it as a mark that, no matter what, I stand on the right side of history.”

Wasik Sajid Khan, a young faculty member at the University of Dhaka, says, “Mine is an original Palestinian/Arab one, which I got from Canada as a gift from my friend. To me, it’s an expression of solidarity. Solidarity with not only the Palestinians, but also with all the rebellious brothers and sisters who are fighting for their rights.”

Even from abroad, the emotional thread continues. Tauhid Tanjim, a Bangladeshi PhD student at Cornell University, says, “Wrapping the keffiyeh around my neck connects me to generations fighting for justice, and reminds me I’m standing on the right side of history. I wear a keffiyeh to stand with Palestinians who refuse to be erased from history by an apartheid state.”

The keffiyeh, once regional and rustic, has become a digital-age totem. On Instagram, TikTok, and X (formerly Twitter), it’s everywhere—draped on shoulders, layered over keffiyeh filters, paired with hashtags like #FreePalestine and #EndTheOccupation. Dr Alam, however, cautions against empty gestures. “Online activism, often labeled ‘slacktivism,’ is sometimes criticised for being performative,” he acknowledges. “But it can also amplify causes, educate audiences, and influence real-world outcomes when done thoughtfully. The keffiyeh’s distinct black-and-white pattern is instantly recognisable as a symbol of Palestinian identity and resistance, especially since its global adoption in the 20th century. Posting photos wearing it on platforms like X, Instagram, or TikTok can introduce or reinforce awareness of the Palestinian struggle. In 2023–2024, posts about Palestine on X often paired keffiyeh imagery with calls to learn about apartheid policies, amplifying educational impact.”

The result? A booming keffiyeh market in Bangladesh. At Baitul Mukarram Market, vendors report a tenfold increase in sales. “Most of my buyers are young people,” one seller says. “They want to express solidarity with our Palestinian brothers.” The scarves—imported from China, India, Saudi Arabia and the UAE—have nearly doubled in price. A piece that once sold for Tk120 now fetches Tk250. “Before the war in Gaza, we sold 15–20 a day. Now the number has gone up to 200,” the vendor says with a mix of surprise and pride.

Online, the keffiyeh has also become a fashion and political statement. Shops offer various patterns and materials, though street stalls remain the most affordable.

Still, not all keffiyehs are equal in meaning. Dr Alam recalls his first—gifted by a Palestinian refugee who visited Chobi Mela. Another favourite came from Miko Peled, the Israeli-American peace activist.

And perhaps that’s the most powerful truth. To wear a keffiyeh today—whether in Gaza, London, or Dhaka—is to join a centuries-long conversation. It’s to wrap oneself in a legacy of defiance, of hope, of the unwavering belief that dignity is worth fighting for.

On World Keffiyeh Day, the scarf speaks louder than ever. And in the streets of Dhaka, it’s saying, We are watching. We remember. And we stand with Palestine.