The Great Gatsby turns 100— and why it remains the most misunderstood novel of all time

The Great Gatsby turns 100— and why it remains the most misunderstood novel of all time

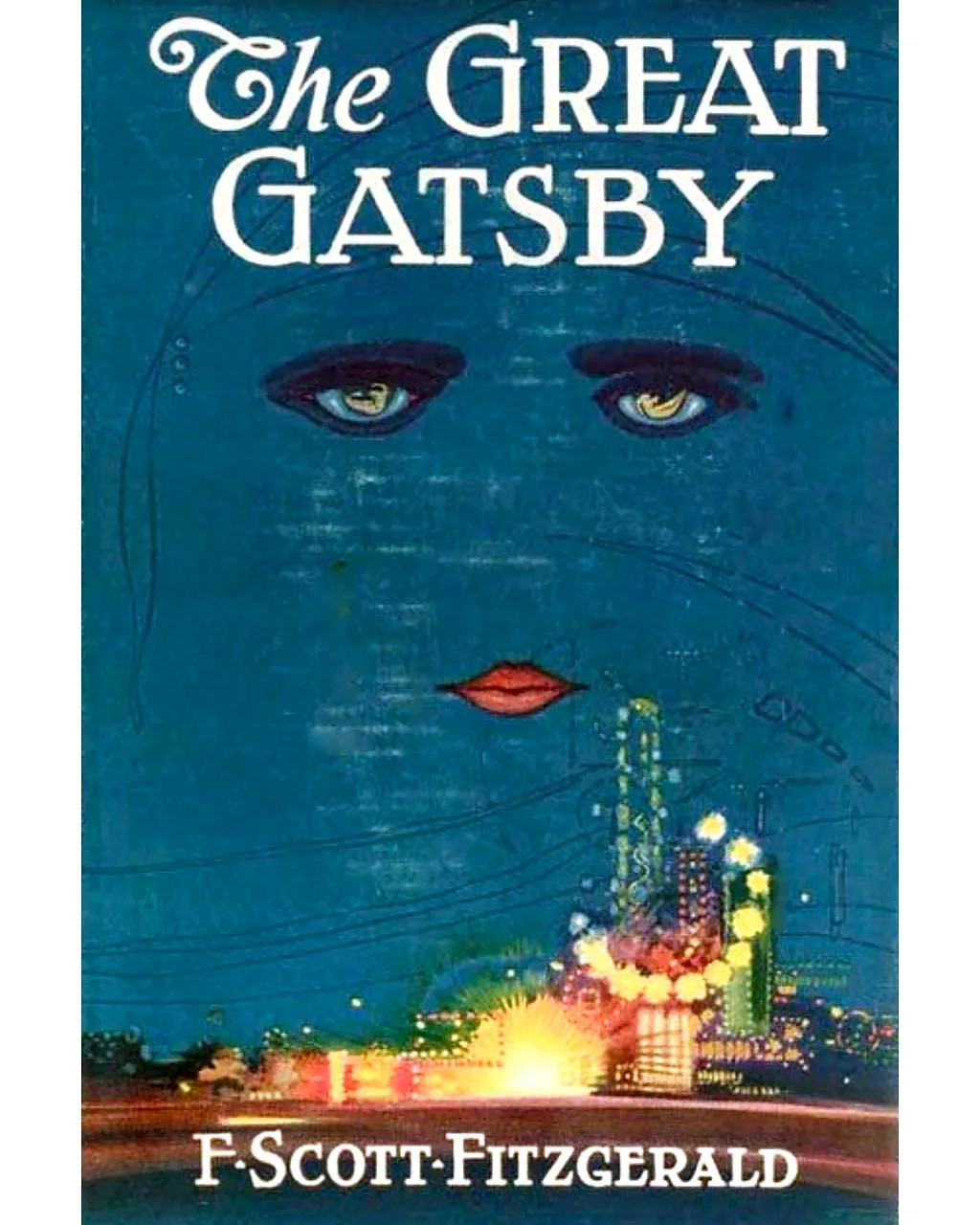

Few literary characters capture the spirit of an era quite like Jay Gatsby does the Jazz Age. Nearly a century since he first appeared on the page, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s tragic dreamer has become a cultural shorthand for flappers, champagne fountains and glittering excess. But The Great Gatsby’s association with glam and grandeur is just one of many misconceptions that have followed it since its original publication in April 1925, reports BBC.

So complete is Gatsby’s detachment from the text that birthed him that his name now graces everything from luxury condos and boutique hotels to hair wax and a limited-edition cologne. You can even order a Gatsby sandwich—essentially a giant chip butty. And yet, naming anything after Gatsby – formerly James Gatz – feels slightly absurd, if not ironic. Beyond the lavish parties, he’s also a bootlegger entangled in crime, and a deluded romantic whose flashy lifestyle veers into the pathetic. If Gatsby represents the American Dream, he also reflects its fragility and hollowness – a man whose end is both meaningless and violent.

From the beginning, The Great Gatsby has been misunderstood. In a letter to his friend Edmund Wilson, Fitzgerald lamented how none of the early critics grasped the novel’s essence. While literary figures like Edith Wharton admired it, most reviewers dismissed it. The New York World even ran a headline: Fitzgerald’s Latest A Dud. Sales were modest, and by the time Fitzgerald died in 1940, unsold copies of the second print run had long been discarded.

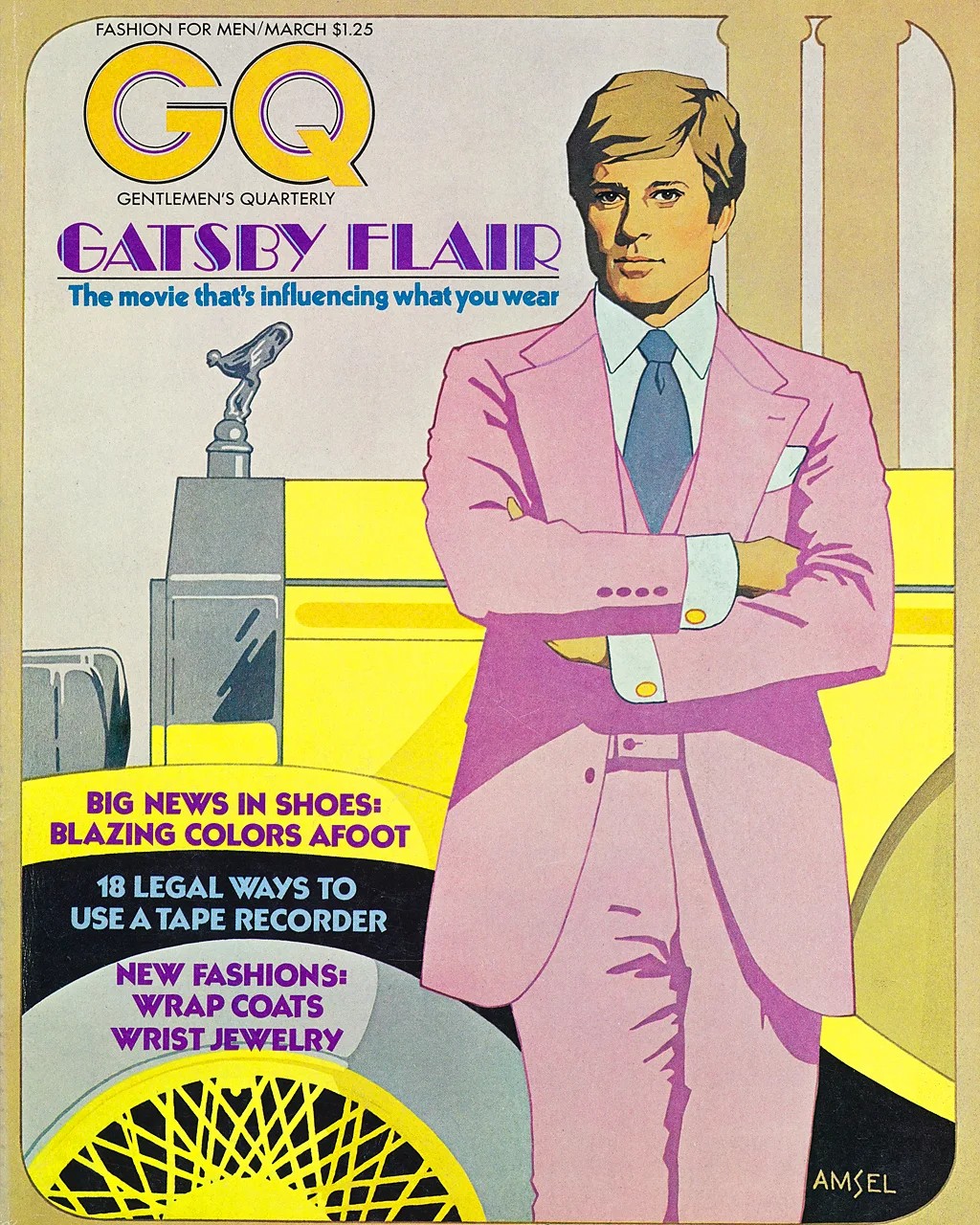

Gatsby’s posthumous rise began during World War II, when nearly 155,000 copies were distributed to US troops. The American Dream gained cultural traction in the 1950s, and by the 1960s, the novel had become a classroom staple. Hollywood helped cement its status: the term “Gatsbyesque” emerged a few years after Robert Redford starred in the 1974 adaptation.

Since then, Gatsby has permeated pop culture—from Baz Luhrmann’s extravagant 2013 film to graphic novels, immersive theatre, and multiple stage musicals. With its copyright expiring in 2021, adaptations exploded. A musical with songs by Florence Welch premiered recently, and a Tony-winning production is still running on Broadway. Writers like Min Jin Lee and Wesley Morris have penned new introductions, while modern retellings are adding new layers to the familiar tale.

While some of these reinterpretations risk reducing Gatsby to party kitsch, others offer deeper readings. In Nick, author Michael Farris Smith imagines a backstory for narrator Nick Carraway, tracing his wartime trauma and disorientation upon returning to a changed America. Smith, who first read Gatsby in high school and found it underwhelming, re-read it abroad in his late twenties. “It was a surreal experience,” he recalls. “Every page seemed to speak to me.”

Smith points to Hemingway’s comment in A Moveable Feast—”we didn’t trust anyone who wasn’t in the war”—as a key to understanding Nick. In Smith’s telling, Nick returns from World War I shaken and hollowed, more detached than cynical. “Maybe it’s not the champagne and the dancing,” Smith says, “but those feelings of uncertainty and instability that keep Gatsby relevant.”

Literature professor William Cain of Wellesley College agrees. Nick’s ambivalent narration, he argues, is central to the novel’s complexity. “We understand Gatsby only through Nick, whose view is both admiring and critical, sometimes bordering on contempt.”

Cain, too, first read the novel as a student in the 1960s, when classroom discussion centred on symbols like the green light or Gatsby’s car. He believes the novel’s depth often gets lost behind its cultural iconography. “We must engage with the actual page-to-page writing,” he says, “not just use the novel as a vehicle to discuss big American themes.”

He re-reads the novel every few years, but it often stays with him in between. In 2020, for example, he thought of Gatsby when President Biden spoke of the American Dream at the DNC. Fitzgerald understood that dream’s allure – and its unattainability. “It inspires enormous effort, but remains out of reach for many,” Cain notes. Gatsby’s wealth cannot erase the social boundaries that ultimately doom him.

Some aspects of the novel have aged poorly. Fitzgerald critiques Tom Buchanan’s white supremacy but still uses racial slurs. Female characters are shallowly drawn, lacking autonomy and existing mostly through the lens of male desire. But these limitations have opened space for reimaginings. Jane Crowther’s novel Gatsby reimagines Jay as a woman and flips the gender roles. Claire Anderson-Wheeler’s The Gatsby Gambit introduces Greta Gatsby, a younger sister caught in a murder mystery.

What remains remarkable is how The Great Gatsby continues to evolve. A teenager reading it sees a different book than a reader in their thirties or forties. When Smith finally published Nick in 2021, he reread Gatsby one more time. “It’s a novel that will keep changing with me,” he says. “That’s what great novels do.”