'Successfully rescued' or 'forcefully removed'? Reclaiming Bangladesh’s rivers prove difficult for crocodilians

Crocodilians are ancient creatures. Allowing room for them will ensure room for many. Working for wildlife but not ensuring human-wildlife coexistence means conserving wildlife on life-support

'Successfully rescued' or 'forcefully removed'? Reclaiming Bangladesh’s rivers prove difficult for crocodilians

Crocodilians are ancient creatures. Allowing room for them will ensure room for many. Working for wildlife but not ensuring human-wildlife coexistence means conserving wildlife on life-support

I remember a river. I remember her lithe course, swerving curves and slender banks. She was carrying snowmelt, crystal-clear rapids. Under the first light, her waves glistened like diamonds. I recall shoaling mahseers chasing minnows, breaching the surface, and flashing their bright golden backs.

There were two gharials, leisurely basking on the beige dunes of the far side, but with keen intent to get one of those frenzied mahseers. Their demeanour, with long snouts, symmetrical spiky scales, and powerful tails, looked mystical.

A few metres away, I remember a large crocodile. Except for its big gaping jaws studded with sharp teeth, the crocodile was otherwise as stiff as an old log, enjoying the heat. There were at least three pairs of periscopic crocodilian eyes, intermittently breaching. With the sun going up, the river welcomed more activities — boatmen ferrying tourists while tourists, on the boats and around me, cheered at the crocodiles and gharials.

Beyond the far bank began the realm of elephant grass merged with the horizon. There was, in fact, an elephant. I crossed the river and noticed a fresh pugmark, left by a tiger the night before.

Later that evening, the far side went silent; a sloth bear came by. Everyone was enthralled by the inquisitive bear as it dug for termites.

Vibrant stalls, food courts and colourful tarps dotted the bank where I was standing and marked the end of a tourist town. The river offered harmony where everybody minded their own business and kept a respectful distance from great beasts. She goes by the name Rapti near Chitwan National Park in Nepal.

Bangladesh has its rivers, the Ganges, the Jamuna, the Meghna, and their tributaries forming a spider-web network traversing the delta. They are far more formidable, revered as deities by many. But there are things these rivers lack compared to the Rapti.

Firstly, no great beasts now live by the Bangladesh rivers. Their expansive banks, interspersed with dunes and grasslands, remain perpetually empty. It sounds analogous to the great forests of Southeast Asia; they run mile after mile, but all the great beasts are gone.

And there is no harmony. Whenever any wildlife ventures into their once-ancestral home, they are immediately marked as a threat. Chaos ensues. These animals are often chased, trapped, beaten and, if luck is in favour, get rescued.

But who is being rescued here and from whom? The line gets blurry and confusing.

Crocodilians are among the most ancient wildlife dependent on river systems. Their existence predates the formation of several rivers and the emergence of men.

Characterised by the long snout, powerful tail, long body and spike-like scales, alligators, crocodiles, caimans, and gharials are the living members of a group that evolved 72.1 million years ago. Bangladesh used to have three different species: saltwater crocodile, marsh crocodile, and gharial. Only the salties now live in the Sundarbans.

Crocodiles survived all five great extinction events. It is in their genes to try and squeeze into the ongoing Anthropocene, the human-induced extinction event.

The great rivers do not follow any boundaries, neither do these ancient creatures. So, after the monsoon, people in localities around southwestern Bangladesh often discover unusual logs floating in the river or lying on the banks. These logs can move.

The ensuing events follow a familiar script. As with nilgais, elephants or fishing cats, upon being spotted, these crocodilians are immediately perceived as dangers. Thousands of onlookers gather as the news spreads like wildfire, aided by misinformation, Facebook reels, and TikTok videos.

Curious youths, energised by survival documentaries, jump in to catch the beast. Assigned personnel arrive a bit late, after completing back-and-forth rounds to get approval from higher authorities.

Lacking proper equipment and manpower, they struggle to maintain the crowd and contain the beast. Crocodiles are cold-blooded creatures. Their energy is limited. After a few good hours, the muddied and often bloodied crocodiles give in, entangled in nets. The end scene, afterwards, is chaos. The specimens are then moved to some enclosure, ‘successfully rescued’. But from whom?

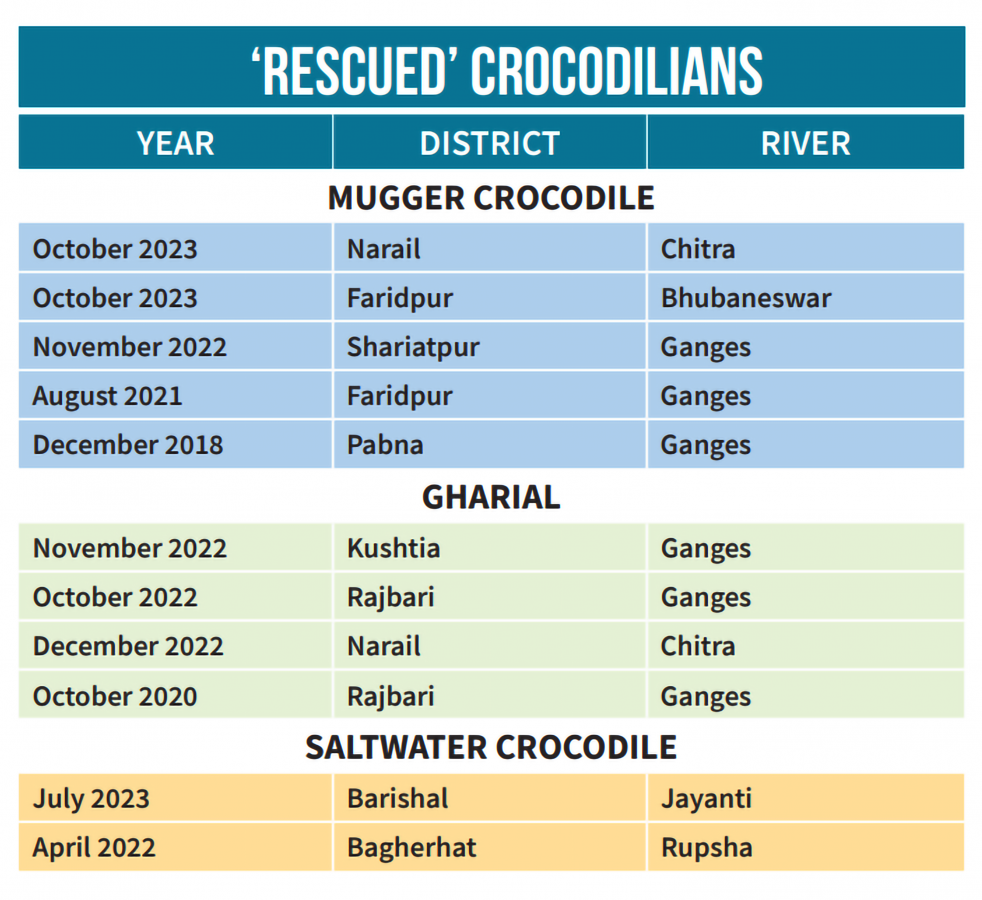

Mugger crocodiles were considered extinct. In 2018, after 50 years, one was ‘rescued’ near Pabna. Last year, two more individuals were similarly ‘saved’, one near Kushtia, and another further downstream near Shariatpur. In the last month, three more similar events have taken place. Two crocodiles were ‘rescued’ from Narail and one from Faridpur.

Gharials are critically endangered. However, every year, individuals of varying sizes are likewise ‘rescued’. For example, this year, one individual was captured from Rajbari. Last year, a 7-foot-long specimen was caught near Narail. The year before, a juvenile was captured from the same place.

A study by the zoology researchers of Dhaka University, published in The Herpetological Bulletin this year, documented 14 events of gharial encounters between 2016 and 2021. All these events come from a region dominated by the Ganges, the last true river-dominated wetland network in Bangladesh.

Are muggers and gharials deadly? Gharials, an ancient species of crocodilian, are specifically built for capturing fish. Unless startled or handled, they stay away from human contact. Practically, there is no record of human fatality from gharials.

Muggers, on the other hand, are among the most docile crocodile species. Across the species’ range that spans from Iran to northern Myanmar, between 2008 and 2013, CrocBite, a global database of crocodile attacks, registered 110 attacks; of which, one-third were fatal. Such muggers were huge and we do not have those specimens anymore.

In certain cases, gharials were released back to the river, branded, ”Gharials are not harmful to humans.” While this is certainly true, are we relaying the right message? Should this be the only criterion to classify wildlife? Do muggers have no place in our rivers? Upon arrival in Bangladesh, are they destined to live in pens? What if all of our enclosures become full of them?

This is not a sustainable strategy. We need to work out a solution to the coexistence of humans and wildlife. Muggers can be harmful, yes. But if Nepal can do it, why can we not achieve this? I remember our goal always shadows the best countries in the world.

Consider the harmless nilgais, peacocks, and fishing cats. In Bangladesh, the tendency is simple: whatever unfamiliar moves, capture it and relocate it. As I was finishing this, I noticed two more news reports where fishing cats were marked as ‘tiger’ and ‘tiger-cub’; the ‘heroism’ of the locals was highlighted with a chained and half-dead fishing cat weakly protesting for life. So, yes. We also need to work with media outlets. There have been attempts to mend mindful headlines and news. But the output has so far been negligible.

Crocodilians are ancient creatures. Allowing room for them will ensure room for many. Working for wildlife but not ensuring human-wildlife coexistence means conserving wildlife on life-support.