Undervalued and underpaid: The silent struggle of Bangladesh's teachers

Undervalued and underpaid: The silent struggle of Bangladesh's teachers

School teachers are the backbone of the education system, and by extension, the backbone of an entire nation.

But in Bangladesh, they remain an overlooked and underappreciated segment of the workforce. Their crucial role in shaping future generations is often overshadowed by a host of systemic issues, including poor pay scales, lack of social recognition, and an unattractive career path for many university graduates.

Despite significant government investments in educational infrastructure, the development and welfare of teachers remain neglected.

The pay dilemma

One of the biggest challenges faced by school teachers in Bangladesh is their low pay; most teachers, especially at the primary level, earn salaries that fail to reflect the importance of their work.

While government school teachers are slightly better off, their counterparts in private institutions earn even less.

As a result, many teachers are forced to take on multiple jobs just to make ends meet.

Compared to other government employees, school teachers rank low on the salary scale. They are often placed on the same pay grade as clerical staff, which is nowhere near the compensation and benefits enjoyed by doctors, engineers, or civil service officers.

Teachers, in general, are still classified as third-class employees when it comes to pay, with some of the lowest salaries in the world.

For example, an assistant teacher at a non-government high school, under the Monthly Pay Order (MPO) scheme, earns Tk12,500 a month, with 10% deducted for retirement benefits.

In government primary schools, a teacher earns Tk19,000, while an assistant teacher in Grade 13 of the government’s pay scale earns Tk17,500 a month.

For government-run secondary schools, teachers are paid according to the 10th grade of the national pay scale, with basic salaries ranging from Tk16,000 to Tk38,640. These teachers receive 45% of their basic pay as house rent, a full bonus equal to their basic pay during festivals, and a Tk1,500 medical allowance.

However, teachers under the MPO (Monthly Pay Order) system receive only Tk1,000 for house rent, Tk500 for medical allowance, and just 25% of their basic salary as a festival bonus, in addition to their basic pay.

What’s particularly striking is that, despite the requirement of a three-year degree or honours certification, primary and secondary teachers often earn less than other jobs that only require a high school diploma. This glaring pay gap further diminishes the appeal of teaching as a profession.

Education experts and teachers’ unions say that the government’s vision of providing quality education will remain unachievable unless it addresses the issues of teachers’ pay.

Regarding the call for an increased payscale, educationist Dr Manzoor Ahmed, emeritus professor at Brac University, said, “This issue has persisted for quite some time, and I believe the teachers’ protests are entirely justified. We’ve already formed a committee to develop a sustainable solution. In my view, we should introduce incentives and revise the overall payscale, not just for primary school teachers but for secondary school teachers as well.”

Lack of social recognition

Compounding the problem of poor pay is the lack of social recognition.

In Bangladesh, professions like medicine, engineering, and government services are held in high regard, while teaching is often seen as a “fallback” option. School teachers do not enjoy the same level of respect as other professionals, despite their critical role in the nation’s development.

This lack of recognition is not limited to social interactions but extends to institutional treatment as well.

Teachers often feel marginalised, with little say in policy-making or educational reforms. They are expected to follow rigid curricula and meet increasing demands from the government and educational boards without receiving adequate support or appreciation.

The public perception that teaching is an “easy” job further diminishes the value of their work, pushing talented individuals away from the profession.

Given these circumstances, it is no surprise that university graduates do not find teaching an appealing career path.

In a country where competitive sectors like IT, banking and engineering offer higher pay, better benefits and greater social status, teaching seems unattractive for those seeking financial stability and professional growth.

Many graduates are also discouraged by the lack of career progression in teaching.

Unlike other professions where employees can move up the ladder, school teachers often find themselves stuck in the same position for years, with limited opportunities for advancement.

Infrastructure over teachers

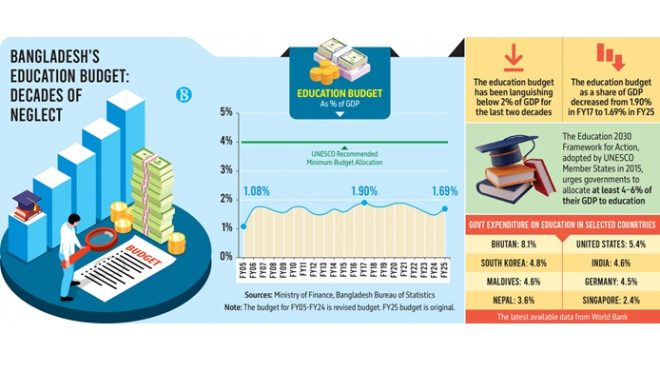

In the last budget, the government allocated around 2% of its GDP to the education sector, considered quite low by global standards.

Furthermore, most of this spending goes toward developing educational infrastructure, with very little directed toward increasing teachers’ salaries.

In the last 15 years, the previous government made significant investments in building new schools, upgrading existing facilities and incorporating digital technologies into classrooms.

But critics argue that it is a flawed approach that will not yield little long-term benefits.

This puts the education system in Bangladesh at a crossroads.

While the government’s infrastructure investments have been on a roll, the real change will only come when school teachers receive the pay, recognition, and support they deserve. Investments in infrastructure often meant a way for the ones in power to gain wealth through corrupt practices.

Without addressing these fundamental issues, the teaching profession will continue to be unappealing to university graduates, and the nation will struggle to build a robust, future-ready education system.

To attract and retain talented individuals, the government must focus on improving pay scales, providing better training and career development opportunities, and raising the social status of teachers. Only then can Bangladesh hope to create an education system that not only looks good on the outside but is also strong and sustainable from within.