Running through time: A 1967 Volkswagen Beetle that outlived war and turmoil

Dr Kamrul Islam’s 1967 Volkswagen Beetle has lived through war, unrest, fire, and decades of use. It now stands as a treasured heirloom and a witness to Bangladesh’s untold stories.

Running through time: A 1967 Volkswagen Beetle that outlived war and turmoil

Dr Kamrul Islam’s 1967 Volkswagen Beetle has lived through war, unrest, fire, and decades of use. It now stands as a treasured heirloom and a witness to Bangladesh’s untold stories.

Some cars are preserved because they are rare. Some because they are beautiful. But there is a small, special category of machines that survive because someone refuses to let them go, even when everything else around them falls apart.

Dr Kamrul Islam’s 1967 Volkswagen Beetle belongs there. It has endured a Liberation War, mass unrest, fire, breakdowns, and the ordinary wear of passing decades. Today, it stands not only as a cherished family heirloom but also as a reminder of the quiet, unrecorded stories that shaped Bangladesh.

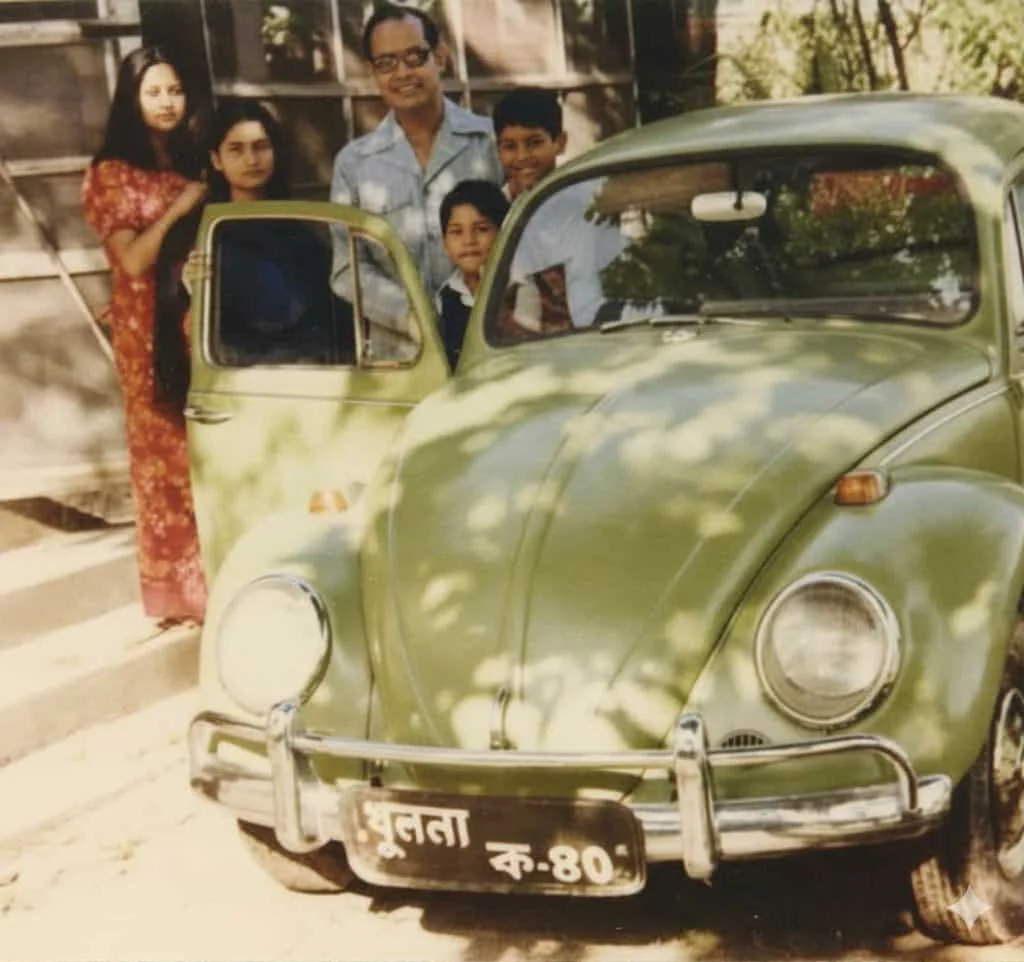

Kamrul, now a doctor like his late father, Professor Dr A I M Mafakhkharul Islam, grew up with this Beetle as an extension of home. His earliest memories involve its rounded fenders, the hum of its rear-mounted engine, and long drives with his father through the greener parts of the country.

“My dad bought it in 1968,” he said. At the time, his father was working in Sylhet. The car’s previous owner, a Pakistani civil service officer, was preparing to leave for Pakistan as political tensions between the two wings of the country escalated rapidly.

Photo: TBS

The Beetle, only a year old then, quickly became part of the household. It travelled with the family through the various postings of Kamrul’s father—first Rajshahi, then Sylhet again, and eventually Mymensingh. But the story that truly defines the car begins in 1971, when the country was on the verge of rebirth.

A car hidden from an army

By the time the 1971 Liberation War erupted, the Pakistan Army had begun seizing private vehicles across the country. Cars symbolised mobility and escape, which made them threats. Anyone who owned something valuable lived under the constant fear of losing it.

Kamrul’s father, then working as a professor at Sylhet Medical College, found himself facing the same looming danger. One of his senior colleagues, the director of Osmani Medical College, had already been pressured into handing over the office car to the army.

Recognising what might come next, he urged Dr Mafakhkharul to get his family out of the city while there was still time. The safest place, he believed, was deep inside a nearby tea estate in Moulvibazar, where soldiers rarely went. His warning proved tragically prescient—he himself was later found to have been massacred by the Pakistani army.

This moment became part of the family’s collective memory. Kamrul heard it repeatedly from his mother while growing up. “My father escaped at night with the car covered in leaves and branches,” he said. They improvised something that resembled a ghillie suit for the Beetle, layering it in foliage so that patrols in the dark would not recognise its shape. It was an act of both desperation and ingenuity.

Photo: TBS

They set off quietly. The road to the tea estate was tense, dotted with patrols and makeshift checkpoints. At one point, soldiers stopped them and demanded answers.

What saved them remains a mystery to Kamrul even today—”Luck, timing, or perhaps simply the fact that my father could speak fluent Urdu is what spared my family,” he added.

Once inside the tea estate, the family tucked the Beetle away among trees and workers’ quarters. It stayed hidden, silent, waiting for a country to be born.

After independence, the family returned to the city. Many government cars and private vehicles that had been confiscated were either destroyed or abandoned. “According to my dad, they later spotted the office car on the outskirts of the city, but it was left in terrible shape,” Kamrul said. Thankfully, the Beetle survived.

Growing up with a survivor

To the young Kamrul, the Beetle was a companion. He remembers it vividly—not in its original factory white, but in a somewhat eccentric shade of parrot green. “The paint was awful,” he said. “But that’s how it looked throughout my childhood.”

Photo: Courtesy

The car was woven into family routines. Kamrul’s father drove it to markets, tennis courts, and on long trips across the country. His elder sister remembers journeys to Jaflong to buy oranges, loading the car and returning with fruit stacked in the back.

There were dramatic incidents as well. A wheel once detached mid-journey, sending the car into an alarming wobble before his father wrestled it to safety. Another time, the battery terminal under the rear seat came into contact with a metal spring and ignited the seat cushion. His father, ever calm, extinguished the fire with sand and water.

And then there was 1990. Political unrest following General Ershad’s fall brought mobs into the streets. Protesters attacked their house in Mymensingh, vandalising property and setting vehicles on fire. The Beetle fell victim again. “They torched it right in our compound,” Kamrul said. The damage was severe, but once more the car refused to disappear from the family’s life.

Learning to drive the forbidden way

The Beetle also played a mischievous role in Kamrul’s teenage years. “I learned to drive in this car,” he said. “My brother and I used to sneak it out when we were in Year Seven or Eight.” Their father, knowing exactly what two curious boys were capable of, hid the keys. The boys, knowing exactly how their father thought, always found them.

Photo: TBS

They even removed the odometer cable before taking the car out, so the mileage would not give them away. When the Beetle stalled, their friends pitched in, pushing it until the engine sputtered back to life. For many of these schoolboys, the Beetle was their first encounter with German engineering—and certainly their first taste of rebellion.

A long path to restoration

When Kamrul’s father passed away in 2007, the Beetle entered its darkest period. It sat unused under a shed in Mymensingh, gathering rust and dust. The family had no time to drive it, and its condition deteriorated quickly. But the papers remained up to date, thanks to Kamrul’s mother, who maintained them quietly year after year.

By 2009, Kamrul decided he could not let the car die. “I asked my mother if I could restore it,” he said. She agreed immediately.

Getting the car to Dhaka was an adventure in itself. Roads were rough then. Kamrul chose 1 May, hoping the public holiday would mean lighter traffic. But the journey turned into a series of crises. Protesters threatened to attack the Beetle as it passed. The brakes overheated. Then the engine overheated. Near Bhaluka, smoke began pouring from the rear, and the car refused to start again. Kamrul had no option but to tow it on a pickup truck.

Even after reaching Uttara, the trouble did not end. A mechanic’s garage where Kamrul had left the car for quick repairs caught fire. “Luckily, my car was spared. Somehow, it always escapes disaster,” he said.

Eventually, the Beetle was repaired enough to run. It was navy blue at that point, and Kamrul began a full restoration with help from the Volkswagen Club Bangladesh. Parts had to be replaced, panels repaired, electricals modernised, and the alternator upgraded. By 2012, the Beetle was reborn. Since then, it has retained its iconic golden shade, making it stand out even on the most crowded streets of Dhaka.

A demanding companion that refuses to quit

Today, the Beetle still needs constant attention. “Things break all the time. Parts are scarce,” Kamrul said. A few years ago, the engine seized near Trishal on the way to a fitness test. It had to be taken back to Dhaka, where fellow Beetle owner Salam overhauled it. Only then did it return to the road.The car remains sensitive to fuel. It stalls, misbehaves, and occasionally surprises him with new problems. But Kamrul takes all of it in stride. “I will never sell this car as long as I’m alive,” he said. “After me, it goes to my son.”

Photo: TBS

He also raises a concern many classic-car owners share. The burden of taxes—carbon tax, advance income tax, and the multiplier applied for multiple car ownership—makes it “almost unreasonable to preserve a piece of history that carries this kind of story.”

A witness on four wheels

This Beetle is more than a restored classic. It is a survivor that once hid from soldiers under a blanket of leaves, a witness to war, a victim of political unrest, a mentor to two brothers learning to drive in secret, and a stubborn little machine that seems to slip out of disaster every time.

In Victory Month, Kamrul’s Beetle reminds us that history does not only live in textbooks or monuments. Sometimes it sits in a garage, smelling faintly of petrol and old paint, waiting for someone to turn the key and keep the memories alive.