Dharapat: The first Bengali calculator!

Dharapat: The first Bengali calculator!

Press a button, and the screen displays Bengali numerals. Dr Mahmud Hasan has invented ‘Dharapat’, the first Bengali calculator, along with a digital clock named ‘Dharakram’, both using Bengali numerals.

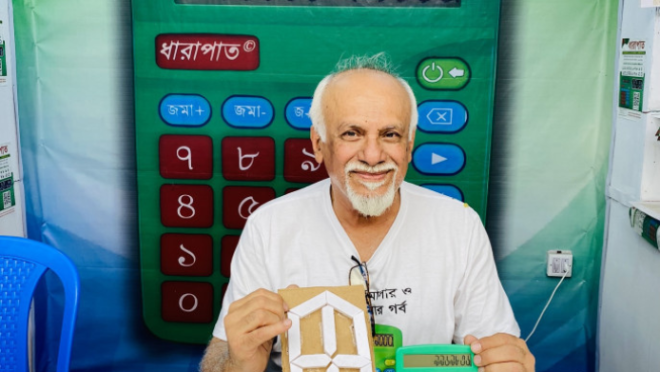

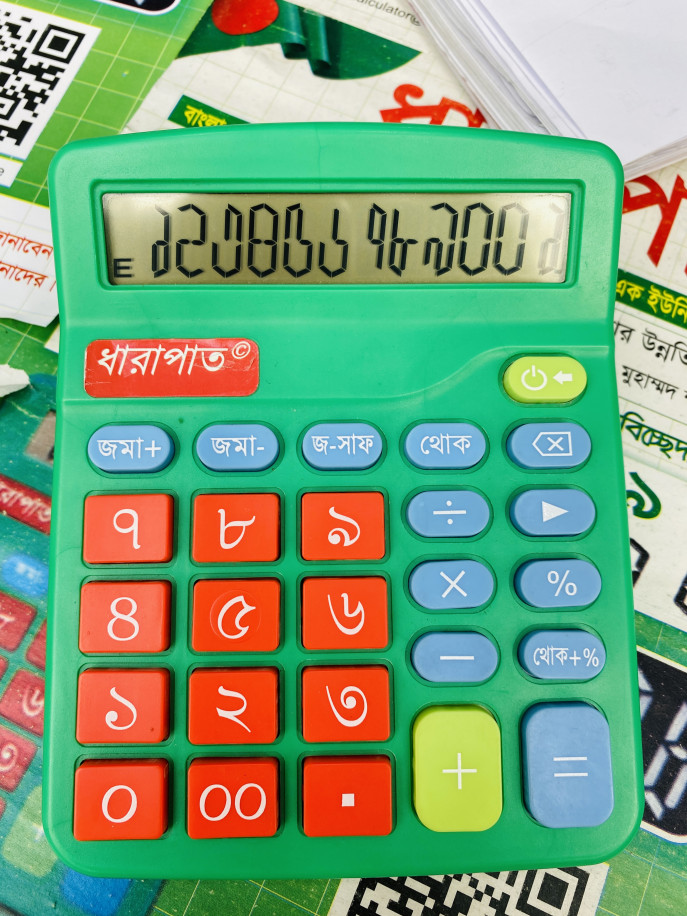

Dr Mahmud Hasan holds a sample of the 12-segment display and the Dharapat calculator. The calculator has a green base with red buttons, each marked in Bengali: ১ (1), ২ (2), ৩ (3), ৪ (4), ‘জমা’ (add), ‘সাফ’ (clear), and ‘থোক’ (total). The design of this first-ever Bengali calculator reflects the red and green of the Bangladeshi national flag.

This year, Dr Mahmud Hasan set up a stall at the book fair inside the Bangla Academy premises. The sign above his stall read, “Dharapat: The First Bengali Calculator.” While this section of the fair is usually less crowded, his stall—tucked in a corner—drew constant attention, especially from children and teenagers.

Dr Mahmud Hasan studied Applied Physics at the University of Dhaka and taught Computer Science and Engineering there from 1985 to 1995. In 1995, he left for Malaysia to pursue a PhD in robotics and never returned to Bangladesh permanently. Over the last 30 years, he has taught at various universities in Malaysia, Brunei, Kazakhstan, and the United States.

Nearly 36 years ago, he dreamt of bringing Bengali numerals into electronic devices. In 1988 and 1989, he conducted research at Bangla Academy on “Advancing and Electrifying the Bengali Typewriter.” His work included developing Bengali fonts, improving Munir Chowdhury’s keyboard layout, reorganising conjunct letters on the Bengali keyboard, and working on the BASCII (Bangla Academy Standard Code for Information Interchange) project.

As part of this research, he envisioned a calculator displaying Bengali numerals. Traditional digital screens use a 7-segment display to form English numbers, but Bengali numerals are more complex and could not be accurately represented this way. To solve this, he developed a 12-segment display capable of rendering Bengali digits from ০ (0) to ৯ (9). The calculator can also switch to English numerals, but this remains a hidden feature, as Dr Mahmud prefers that the device be used primarily in Bengali.

In 1988, he applied for a government grant of Tk50,000 to fund the project, but his request was denied. Undeterred, he continued working independently, finally launching Dharapat in 2025. It took years of effort to find a cost-effective way to manufacture it.

Although he showcased the Bengali calculator at this year’s book fair, he did not sell any units. Production remains limited, and his goal was to gauge public interest. He noted an overwhelmingly positive response, especially from children. “Almost 95% of visitors wanted to buy it. Many were disappointed when they found out it wasn’t for sale,” he said. “I’m a scientist, not a businessman. I don’t understand commercial matters well. But if someone is willing to support me in making this widely available, they are most welcome.”

Dr Mahmud designed Dharapat to eliminate the limitations of Bengali numerals in mathematics. Currently, students use English numbers on calculators but must write answers in Bengali, often leading to errors—especially between ৪ (4) and ৮ (8), which resemble 8 and 4 in English. Using a Bengali calculator could prevent such mistakes.

He also believes Dharapat can help children overcome their fear of mathematics. Bengali numerals resemble certain letters—৩ (3) looks like ত (T), ৬ (6) like ড (D), and ৮ (8) like ট (T)—yet, current learning methods fail to integrate these similarities. Switching between English calculators and Bengali writing adds to students’ confusion.

According to him, “Once children gain confidence in their native language, they will feel more comfortable learning other languages, including English.” He noted how India introduces English as a standard language from primary school, whereas Bangladesh lacks such a unified approach. This inconsistency, he believes, contributes to fear of science and mathematics. “I want to see a scientifically-minded Bengali nation,” he said.

Who is this calculator for? “All Bengali speakers,” he replied. “But I believe it will be especially useful for students in grades 7, 8, and 9. I also want to distribute it in rural markets.” He explained that farmers and small-scale business owners, who may struggle with English numerals, could use this device for their daily calculations.

If commercial production begins, Dharapat will cost between Tk350–400. Manufacturing each unit costs around Tk250–270, and Dr Mahmud has no intention of turning it into a profit-driven business.

The outer casing will be produced in Bangladesh, but components like the mathematical processing unit (MPU) and display must be imported from China. The MPU used in Dharapat is the same as that found in Casio calculators, ensuring precision in calculations. Instead of the usual 7-segment display, Dharapat uses 12 segments to render Bengali numerals. It runs on two AAA batteries, lasting up to four years.

Unlike most calculators, Dharapat does not include a solar panel, as adding one would increase the price by approximately Tk60. To keep costs low, Dr Mahmud opted against it.

He intends to keep his invention open-source. He has not patented the 12-segment Bengali numeral display, allowing anyone to use the technology for future innovations. His only goal is to see Bengali numerals widely used in digital devices for the benefit of the people.