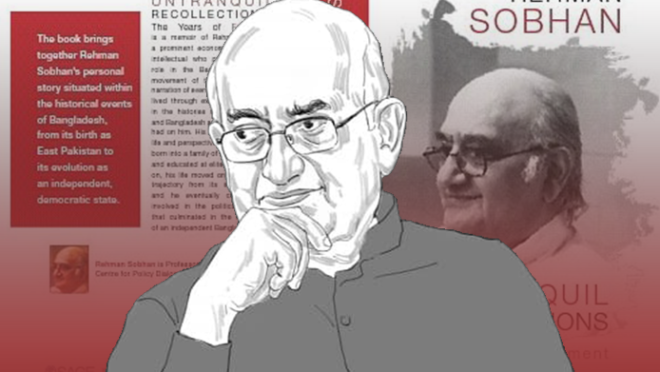

A life woven into history: Rehman Sobhan's Untranquil Recollections

A life woven into history: Rehman Sobhan's Untranquil Recollections

Under the starry nights on 27th March 1971, an economics professor disguised as a refugee is crossing a calm river. His first destination is Bramanbaria en route to Kolkata. He left his lavish house in Gulshan and also abandoned his two sons and wife because had he stayed behind, he surely would’ve been killed, and we wouldn’t get the chance to revisit the birth of Bangladesh through his memoir, Untranquil Recollections.

Freshly out of Cambridge, this individual, having roots in the Dhaka Nawab family on his mother’s side and a hint of Bangalee blood on his father’s side from Murshidabad, faced a life-affirming decision: to join the prestigious Peshawar University in West Pakistan as a lecturer or join the University of Dhaka.

Maybe influenced by his father’s business holdings or some other intuition, this non-Bangalee with no knowledge of the Bangla language, Rabindranath, and never having eaten the famous Hilsha, decided to start his life in the economically deprived nation of East Pakistan. Little did he know in the fateful year of 1957 that he would find his aristocratic persona wearing a lungi with a belt attached to it crossing the border just a few years later.

Untranquil Recollections, the memoir in discussion, is a detailed story of Rehman Sobahn. Born in the elite circles of the subcontinent, his life was meant to pass by just like any other privileged newborn. In the early years of his life, this trend was very apparent as he discussed his days in boarding school, his hobby of cinemas in his vacation days, and his overall upbringing in Kolkata. This part of the memoir is overtly serene, and maybe if not for his later years, this would have remained an inconsequential piece of a family patriarch’s life story, nothing else.

The professor’s inkling towards politics started as he joined Cambridge in pursuing his undergraduate degree in economics. With a recommendation letter from his maternal grandfather, the once Chief Minister of East Pakistan, Khawaja Nazimuddin, he embarked on a life that soon circled around political discussions and readings inspired during his time in England.

Particularly, as he mentioned, he was predictively inspired by the left-leaning rhetoric as one commonly does in his university days. Certain weekly’s, such as The New Statesman, as well as other influential left-leaning publications, shaped his early views on politics. The new statesman would again serve as a friend for the professor when he would express his need for an independent Bangladesh in 1971. After his graduation, the professor made a conscious decision to start his career in academia at the University of Dhaka.

This is where we as readers start to identify certain characters and personalities who paved the way for our final independence. His life, even before coming to Dhaka, was surrounded by influential political figures who at that time were playing their active roles in shaping the politics of East Pakistan.

His own maternal grandfather, Khawaja Nazimuddin, was a prominent Muslim Leaguer who led the call for an independent Pakistan in East Bengal. His wife, Salma, also a professor at Dhaka University had relations with Hossain Shaheed Shahrawardy, one of the principal founders of Awami Muslim League and the Prime Minister of Pakistan.

Through his intricate family ties, his life’s stories are not only stories of his own providence but also a dramatic screenplay that acts as footnotes for Bangladesh’s emergence.

Politics at that time was not a matter of something to be ignored but rather a deeply personal and moral burden upon the people who deemed it necessary to enact influence whenever they saw injustice.

Therefore, the university campus at that time was also filled with different political factions, such as the East Pakistan Students’ League, the Students’ Union, and the moral equivalent of the rascals of Bangladesh Chhatra League today, the Students Federation. An auxiliary force controlled by Moem Khan, then governor, to stifle any movement against the Ayub regime.

The Ayub regime’s decade of development narrative was swiftly debunked by most Bengali intellectuals at that time, and notable among them was Rehman Sobhan, who admittedly in his writings does not take full credit for popularising the concept of One Country, Two Economics.

The chapters that describe his time living in Dhaka in the 1960s are most riveting. It is at this time in the early 60s that the professor would meet Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on two separate occasions, but in two completely different circumstances.

First at his grandfather’s home, Khawaja Nazimuddin, and at the hotel Intercontinental while visiting a wounded West Pakistan ally of Moulana Bhashani, Mia Ifterkharuddin. Meeting the professor in such different political surroundings once at the far right and later on the far left, the Sheikh commented on the ambiguous nature of the professor and acknowledged his presence.

The professor is also a historical landmark when it comes to the students he helped shape. Our only Nobel Laureate, Professor Yunus, was a first-year economics student of his, though Rehman Sobhan hardly takes any credit for Yunus’s later predicament, sarcastically!

His notable other students include the later president of the Bangladesh Communist Party, Muzahedul Islam Selim, the Chief Advisor of the Caretaker Government, Dr. Fakhruddin, the editor in chief of The Daily Star, Mahfuz Anam, and many more.

Such prominence not only in his academic disciples but also in his colleagues such as Dr. Nurul Islam, Professor Abdur Razzaq etc. all shaped him to not be boxed in his usual life just as a university lecturer, but inspired him to take on the establishment, some of whom he shared family ties with.

He was also instrumental in rehashing the famous 6 ponts of the Awami League. The details of autonomous rule and the exchange of goods separately imported and exported were all the nitty-gritties negotiated by a group of pundits on behalf of the Awami League, and as a principal negotiator in that group, Rehman Sobhan detailed the account quite vividly.

As history buffs, this is maybe one of the most detailed surviving accounts of that time of political turmoil. During the 1970 election, the atmosphere around East Pakistan was also recounted by the professor exquisitely.

The future PM of the country, Tajuddin counted on one hand the seats Awami League might lose when questioned by the professor. In these chapters, the professor is expressive in his appreciation for Tajuddin as he considered Tajuddin a teacher of his understanding of the politics of the Bengalees.

The most thrilling portions of the book consist of the chapters from the beginning of March to the day of liberation, 16th December. As known to all of us, the atrocities conducted by the Pak army were presented no less attractively than a well-detailed documentary. The professor had to leave his family behind in search of the unknown, and finally, when he returned, jubilation not only could be felt beyond the account itself but also affected the reader’s hearts. I must say, for a memoir filled with detailed historical accounts, which for some may seem as a source of boredom, it is no less compelling than any thriller.

His writings serve as a historical document and as a piece of cinema, which only a book can do when written in such an elegant style. You’ll be lost in the pages from the point of time you pick it up—can be read in one sitting, no doubt.