Who is a true engineer? Titles, quotas, and frustration

In Bangladesh, the word “engineer” has long been associated with prestige and intellectual rigour.

Who is a true engineer? Titles, quotas, and frustration

In Bangladesh, the word “engineer” has long been associated with prestige and intellectual rigour.

Roads, bridges, power plants, factories, and cities all bear the imprint of engineers’ work. Yet, since mid-2025, the very word has been at the centre of nationwide attention. What began as a technical confrontation over recruitment rules and promotion pathways has now escalated into one of the most divisive student movements.

The conflict has shut down campuses, paralysed traffic intersections, drawn police into clashes with students, and forced the interim government to form multiple review committees, only to ultimately defer the issue. At its core lies a deceptively simple but politically explosive question: who is a “true engineer” in Bangladesh?

The roots of the unrest

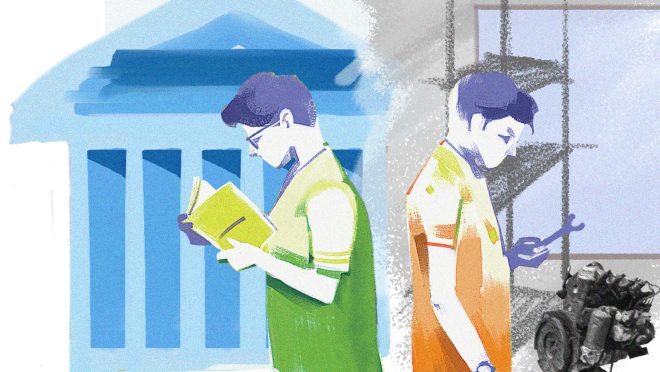

The current unrest lies in the structure of Bangladesh’s technical education system, shaped in the early decades after independence. Government engineering services were designed with a clear hierarchy. Grade-9 posts, typically titled Assistant Engineer, were intended for graduates with a four-year Bachelor of Science in Engineering. Grade-10 posts, usually called Sub-Assistant Engineer, were reserved exclusively for diploma holders — graduates of four-year polytechnic programmes pursued after secondary school.

The rationale was straightforward: degree engineers would handle design, planning, and higher-level decision-making, while diploma engineers would focus on field implementation, supervision, and maintenance.

Over time, this separation eroded. Promotion quotas allowed diploma engineers to rise from Grade 10 to Grade 9 without sitting for open competitive exams. In some departments, diploma holders entered higher ranks through internal promotions and other unprecedented means. Seniority rules further complicated the issue, often resulting in the promotion of diploma engineers ahead of newly qualified degree holders.

The State and the institutions respond

Caught between two powerful and organised groups, the interim government moved to contain the situation. Advisory committees were formed in late August 2025 to hear both sides and recommend solutions.

Government advisers publicly acknowledged the complexity of the issue, stressing that it was not new and could not be resolved hastily.

Professional institutions, however, were less equivocal.

The Institution of Engineers, Bangladesh issued a statement strongly supporting the degree engineers’ position. It called for the abolition of diploma promotion quotas, strict enforcement of qualification-based recruitment, and implementation of existing gazette notifications that allow only BSc graduates to legally use the title “Engineer.”

The Institution of Diploma Engineers, Bangladesh, on the other hand, defended the historical role and rights of diploma engineers, though its influence was felt more through protests and committee participation than through formal policy declarations.

Despite months of discussion, no concrete reforms followed. In January 2026, the Ministry of Education announced that the interim government would not take any binding decision on the matter, leaving the issue to the next elected administration. For many students, this amounted to an admission of political paralysis.

A crisis bigger than titles

While the dispute is framed around grades, quotas, and titles, its underlying causes run deeper. Bangladesh suffers from a chronic mismatch between the number of engineers it produces and the nature of jobs available.

High-value engineering roles in research, design, and advanced manufacturing remain scarce. Government service, with its security and status, becomes the primary battleground, forcing different tiers of technical graduates into direct competition.

This scarcity has broader consequences. Many of the country’s brightest engineering graduates leave for opportunities abroad or abandon engineering altogether in favour of administrative cadres. The state invests heavily in technical education but reaps limited returns, while frustration within the system intensifies.

So who is a true engineer?

In functional economies, this question rarely provokes street protests. Roles are clearly defined, titles are legally protected, and pathways for advancement are transparent. BSc engineers and diploma engineers work as part of an integrated team, each with recognised responsibilities and opportunities for growth.

Bangladesh’s crisis stems not from the existence of two educational tracks, but from decades of policy ambiguity and ad hoc compromises. Until recruitment rules are standardised, professional titles clarified, and genuine upward mobility ensured through education rather than shortcuts, the conflict will persist.

The struggle over who gets to be called an engineer is ultimately a struggle over how Bangladesh values knowledge, skill, and merit. Until that question is answered with clarity and courage, the nation’s campuses and streets are unlikely to remain quiet.