Why almost every book is a “Best Seller”

Why almost every book is a “Best Seller”

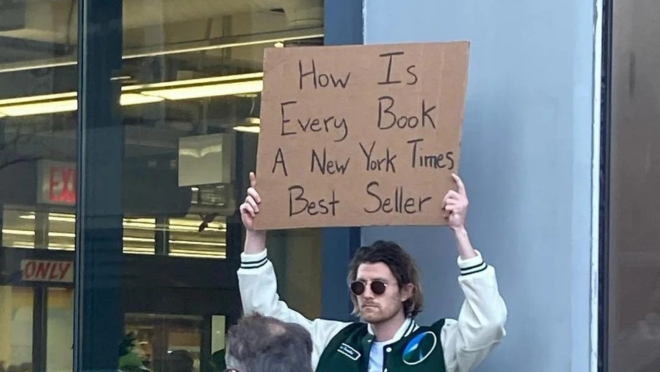

Walk into any bookstore, scroll through an online retailer, or glance at a social media ad, and you’ll see the same phrase again and again: “Best Seller.” Sometimes it’s framed as “#1 Best Seller,” “New York Times Best Seller,” or simply “International Best Seller.” The label is so common it’s almost lost its meaning.

And yet, it’s doing exactly what it’s meant to do.

The idea of a book being a “best seller” once signified rare achievement like for instance a sign of cultural relevance, strong sales, and wide readership. But today, it’s less a reflection of popularity and more a tool of perception. The rise of self-publishing, targeted marketing, and fragmented sales charts has created a situation where almost any book can, at some point, earn the title “best seller” even if only for a few hours, in a very specific category, or on a very loose and wide list.

So how did we get here?

The phrase “best seller” has no official definition. There’s no global threshold for how many copies a book must sell to earn the label. Instead, it depends entirely on where and how the book is sold.

For example, Amazon updates its best seller rankings hourly. With thousands of categories—from “Mystery & Thrillers” to “Outdoor Cooking”—it’s possible for a book to top a niche chart with just a handful of sales. If your eBook is the most downloaded in the category “Teen & Young Adult Short Stories” for a few hours, you can technically say it was a “#1 Amazon Best Seller.”

This is perfectly legal, and increasingly common. Many self-published authors (and some traditional ones) design their launch strategies around these algorithms. They pick obscure categories, rally their audience for a coordinated buying push, and then claim the title once they briefly top the list.

The term may be accurate in a literal sense, but it’s misleading in spirit. Readers might assume a “best seller” has sold hundreds of thousands of copies. In reality, it could be under a hundred.

Then there’s the more traditional route: landing on a list like the New York Times Best Sellers. These lists do carry weight, but even they’re not as straightforward as they seem.

The New York Times list, for instance, isn’t purely based on sales figures. It uses a secretive methodology that includes sales from a curated selection of bookstores and retailers. It also weighs things like geographic diversity and may exclude bulk orders, meaning if a company buys thousands of copies of its own CEO’s book, it won’t necessarily make the list.

Because of this, it’s possible for a book that outsells another to be left off the chart. It’s also why some authors spend tens of thousands of dollars to engineer a bestseller campaign. They hire consultants, arrange staggered purchases, and work with retailers to maximise the chances of hitting the right thresholds. Success doesn’t always mean mass appeal, it can also mean a well-executed plan.

Once a book hits any version of a best seller list, the label becomes permanent. Publishers put it on the cover, authors add it to their bios, and future buyers are influenced by it, even if the book barely stayed on the list for a single week.

This marketing loop reinforces itself. Readers are drawn to best sellers because we assume others have liked them. Retailers feature best sellers more prominently, which boosts visibility and drives more sales. Eventually, the label becomes less about what has sold well and more about what might sell well.

Even traditional publishers aren’t immune to the inflation of the term. You’ll sometimes see new releases described as the “latest from the best-selling author of…” even if that author’s prior success was modest or confined to a niche. The phrase “best-selling” adds credibility, even if it’s built on thin technicalities.

At its core, “best seller” is an appeal to trust. It tells the reader: “Other people have bought this. You should too.” In a crowded marketplace, that kind of social proof matters. It reduces the risk of picking a bad book, especially when readers are overwhelmed with choice.

This is why the label works so well, even if it’s diluted. It taps into something fundamental about how we make decisions, especially when it comes to subjective experiences like reading.

The irony is that many genuinely great books never earn the label at all. They build their audience slowly, through word-of-mouth, critical praise, or long-term relevance. They don’t spike in a single week; they endure. But endurance doesn’t make for a flashy headline.

So, should you ignore the “best seller” badge entirely? Not necessarily. But it helps to approach it with skepticism. Ask yourself where the claim comes from. Was it an Amazon category spike? A legitimate spot on the New York Times list? Or is it simply part of the book’s branding?

More importantly, don’t let the label drive your decisions. A best seller might be worth reading, but so might a quiet debut with no marketing budget. Trust your instincts. Read reviews. Sample the first few pages.

Because in the end, a book’s true value isn’t measured by its sales chart, it’s measured by what it does for the person reading it. And that’s something no algorithm can rank.